The latest soda industry PR ploy: 20% less soda by 2025

The Alliance for a Healthier Generation (founded by the American Heart Association and the Clinton Foundation) and the American Beverage Association (funded mainly by Coca-Cola and PepsiCo) jointly announced this week that the major soft drink companies were pledging to reduce beverage calories consumed per person nationally by 20% by 2025.

The Alliance, Coca-Cola, Dr Pepper Snapple, PepsiCo, and the American Beverage Association placed a full-page ad in yesterday’s New York Times:

This is a tremendous undertaking by the industry, one that should be applauded, and also one that will not come easily. The industry will leverage every ounce of their national and local influence, product innovation and marketing muscle to reach this ambitious and necessary goal. And when this goal is reached, we believe it will not only signal a shift in access to reduced-calorie options, but also a positive shift in consumer interest in these no-and lower-calorie options.

The New York Times quotes former president Bill Clinton (it also quotes me*):

This is huge…I’ve heard it could mean a couple of pounds of weight lost each year in some cases…in low-income communities, sugary sodas may account for a half or more of the calories a child consumes each day.

In a statement, Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, said:

We congratulate the Alliance for a Healthier Generation and the beverage industry for continued action towards reducing the beverage calories consumed by people across the United States. We are especially pleased that this commitment will target communities with disproportionately high consumption rates of sugar-sweetened beverages. We look forward to working with the Alliance and beverage industry to measure and monitor the impact of this commitment on the health of our country.

Despite the congratulations, I can’t take this as anything more than public relations.

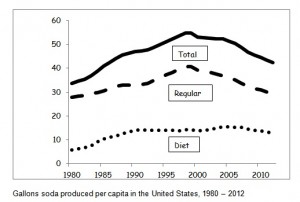

Soda sales are going to decline by that much anyway.

Although the Alliance says the companies will do this through national initiatives to educate consumers about smaller portions, lower-calorie beverages, and water, and to focus these efforts in lower income communities, they really don’t have to do a thing.

All they have to do is wait for these trends to continue. The Times quotes me on this point:

While they’re making this pledge, they are totally dug in, fighting soda tax initiatives in places like Berkeley and San Francisco that have exactly the same goal,” said Professor Nestle, who has just finished a book about the industry.

Here’s what I mean:

The American Beverage Association and soda companies are putting millions into fighting soda tax initiatives in San Francisco and Berkeley.

As the Center for Science in the Public Interest says, if the soda industry really were serious about helping Americans drink less of sugary products, it

could accelerate progress by dropping its opposition to taxes and warning labels on sugar drinks. Those taxes could further reduce calories in America’s beverage mix even more quickly, and would raise needed revenue for the prevention and treatment of soda-related diseases.

And, CSPI says, the soda industry should stop opposing and, instead, should support Representative Rosa DeLauro’s Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Act of 2014 (the SWEET Act), which aims to tax caloric sweeteners. This would raise $10 billion a year to help prevent and treat diseases caused by excess soda consumption.

But the CEO of Pepsi says the soda industry isn’t getting enough appreciation for its efforts to counter obesity.

Politico ProAg‘s Helena Bottemiller Evich reports that at a meeting sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) to applaud the soda industry’s announcement, Indra Nooyi, PepsiCo’s CEO,

expressed frustration with the endless criticism from activists who blame much of the obesity epidemic on the food industry despite what she sees as significant progress from the biggest brands in America…“Why not give industry a compliment and then talk about the next step?…We have now stemmed the growth in calorie consumption, which is huge…I look at those trends and think industry has done pretty well, as a whole.

Why the RWJF, a major funder of initiatives to counter obesity, seems so cozy with Pepsi is curious.

The coziness is especially curious because of Mrs. Nooyi’s “We.” If the industry is “doing well,” it’s because health advocates, some of them funded by RWJF, have forced soda companies to change their practices.

The one significant accomplishment: an admission that sodas contribute to obesity

As the Wall Street Journal puts it,

The move is an implicit acknowledgment by the soda industry that longtime staples like Coke, Pepsi-Cola and Dr Pepper have played a role in rising obesity rates.

Now that really is a sign of progress.