Tuesday’s election: Food politics at issue

My monthly (first Sunday) Food Matters column in the San Francisco Chronicle deals with the implication of Tuesday’s election for food politics.

Q: Neither of the presidential candidates is saying much about food issues. Do you think the election will make any difference to Michelle Obama’s campaign to improve children’s health?

A: Of course it will. For anyone concerned about the health consequences of our current food system, the upcoming election raises an overriding issue: Given food industry marketing practices, should government use its regulatory powers to promote public health or leave it up to individuals to take responsibility for dealing with such practices?

Republicans generally oppose federal intervention in public health matters – witness debates over health care reform – whereas Democrats appear more amenable to an active federal role.

The Democratic platform states: “With prevention and treatment initiatives on obesity and public health, Democrats are leading the way on supporting healthier, more physically active families and healthy children.”

Policy or lifestyle?

In contrast, the Republican platform states: “When approximately 80 percent of health care costs are related to lifestyle – smoking, obesity, substance abuse – far greater emphasis has to be put upon personal responsibility for health maintenance.”

At issue is the disproportionate influence of food and beverage corporations over policies designed to address obesity and its consequences. Sugar-sweetened beverages (sodas, for short) are a good example of how the interests of food and beverage corporations dominate American politics.

Because regular consumption of sodas is associated with increased health risks, an obvious public health strategy is to discourage overconsumption. The job of soda companies, however, is to sell more soda, not less. As a federal health official explained last year, policies to reduce consumption of any food are “fraught with political challenges not associated with clinical interventions that focus on individuals.”

Corporate spending

One such challenge is corporate spending on contributions to election campaigns. Although soda political action committees tend to donate to incumbent candidates from both parties, soda company executives overwhelmingly favor the election of Mitt Romney.

As reported in the Oct. 12 issue of the newsletter Beverage Digest, soda executives view the re-election of President Obama as a “headwind” that could lead to greater regulation of advertising and product claims, aggressive safety inspections and characterizations of sodas as contributors to obesity. In contrast, they think a win by Mitt Romney likely to usher in “more beneficial regulatory and tax policies.”

As for lobbying, what concerns soda companies is revealed by disclosure forms filed with the Senate Public Records Office. Coca-Cola reports lobbying on, among other issues, agriculture, climate change, health and wellness, and competitive foods sold in schools. PepsiCo reports lobbying on marketing and advertising to children. Their opinions on such issues can be surmised.

But Coca-Cola also says it lobbies to “oppose programs and legislation that discriminate against specific foods and beverages” and to “promote programs that allow customers to make informed choices about the beverages they buy.”

Lobbyists

Soda companies have lobbied actively against public health interventions recommended by the White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity in 2010 and adopted as goals of Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move campaign to end childhood obesity within a generation.

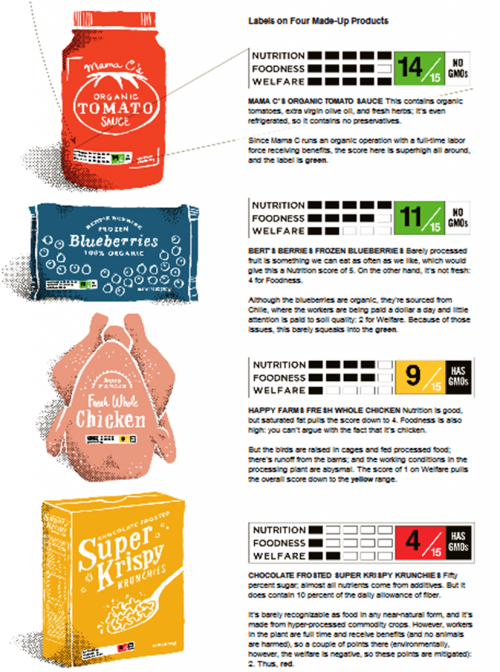

Implementation of several interventions – more informative food labels, restrictions on misleading health claims, limits on sodas and snacks sold in schools, menu-labeling in fast-food restaurants, and food safety standards – has been delayed, reportedly to prevent nanny-state public health measures from becoming campaign issues.

To counter New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s 16-ounce cap on soda sales, the industry invested heavily in advertisements, a new website and more, all focused on “freedom of choice” – in my mind, a euphemism for protecting sales.

Soda tax

Although the obesity task force suggested that taxing sodas was worth studying, the American Beverage Association lobbied to “oppose proposals to tax sugary beverages” at the federal level. The soda industry reports spending more than $2 million to defeat Richmond’s soda tax ballot initiative Measure N, outspending tax advocates by 87 to 1.

In opposing measures to reduce obesity, the soda industry is promoting corporate health over public health and personal responsibility over public health.

Supporters of public health have real choices on Tuesday. I’m keeping my fingers crossed that Let’s Move will get another chance.