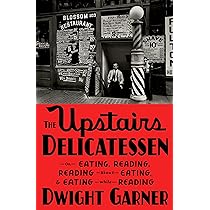

Weekend reading: The Upstairs Delicatessen

Dwight Garner. The Upstairs Delicatessen: On Eating, Reading, Reading about Eating, & Eating While Reading. Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2023. 244 pages.

This book was given to me by my editor at Farrar Straus & Giroux (which is publishing the new edition of What to Eat in 2025).

And what a fun read it is.

For one thing, the title describes exactly how this book is constructed.

Garner (who I don’t know but wish I did) reviews books for the New York Times (his most recent is a review of Fuchcia Dunlop’s history of Chinese food).

He, as it turns out, is one serious foodie.

In this memoir of sorts, he notes what everyone he reads—and he reads everything—has to say about food. The name-dropping result takes getting used to. Here is an example from the chapter on shopping for food.

I push past the onions and put two leeks into my cart. I like to slice off the tops, when cooking with them, and set them on the windowsill, where the crazy tendrils wave like Struwwelpeter’s hair in the children’s book by Heinrich Hoffmann…I take some arugula. In Jonathan Franzen’s novel The Corrections, a failed academic named Chip eats arugula that’s “so strong it made his eyes water, like a paragraph of Thoreau.” Arugula wasn’t well-known in America before the eighties. When farmers began to grow it in California, they didn’t know how much to charge. Cree’s [Garner’s wife’s] father, Bruce explained that in Europe the cost was roughtly equal to a pack of cigarettes. According to Joyce Goldstein, in her book Insie the California Food Revolution, farmers listened to him and initially pegged arugula prices to the cost of Bruce’s Lucky Strikes.

This is all a great introduction to who is writing what about food, and wonderfully gossipy about people I’ve read too (and occasionally have met).

But wait. How come he’s not quoting me?

I went right to the Index’s pages and pages of names.

Bingo! There I am on page 93.

By now we’ve all read our Eric Schlosser, our Alice Waters, our Marion Nestle, our Michael Pollan. These are first-rate writers and thinkers, and God bless them, but they can’t help, at times, sounding sanctimonious.

I am deeply honored by—and adore —being grouped with Schlosser, Waters, and Pollan.

But, ouch. Sanctimonious? Moi?

Oh well. I enjoyed reading the book. A lot.