The latest food politics target: The Thrifty Food Plan

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has released a report complaining about the Biden administration’s update of the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP).

The Thrifty Food Plan (TFP) describes how much it costs to eat a healthy diet on a limited budget, and is the basis for maximum Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. In 2021, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reevaluated the Thrifty Food Plan and made decisions that resulted in increased costs and risks for the reevaluated TFP. Specifically, the agency (1) allowed the cost of the TFP—and thus SNAP benefits—to increase beyond inflation for the first time in 45 years, and (2) accelerated the timeline of the reevaluation by 6 months in order to respond to the COVID-19 emergency. The reevaluation resulted in a 21 percent increase in the cost of the TFP and the maximum SNAP benefit.

The complaint, done at the request of Republican members of the House and Senate, says that “USDA began the reevaluation without three key project management elements in place.”

First, without a charter, USDA missed an opportunity to identify ways to measure project success and to set clear expectations for stakeholders.

Second, USDA developed a project schedule but not a comprehensive project management plan that included certain elements, such as a plan for ensuring quality throughout the process.

Third, the agency did not employ a dedicated project manager to ensure that key practices in project management were generally followed.

USDA gathered external input, but given time constraints, did not fully incorporate this input in its reevaluation.

The GAO agreed, titled its report, Thrifty Food Plan: Better planning and accountability could help ensure quality of future reevaluations, and said ” GAO found that key decisions did not fully meet standards for economic analysis, primarily due to failure to fully disclose the rationale for decisions, insufficient analysis of the effects of decisions, and lack of documentation.

Comment: The Thrifty Food Plan is the lowest cost of four plans (the other three are the Low-Cost, Moderate-Cost, and Liberal Food Plans) developed by USDA to set standards for a nutritious diet.

These were developed by the USDA in the 1930s to provide “consumers with practical and economic advice on healthful eating.” The latest figures for a family of four say that the monthly cost of these plans averages about $683, $902, $1121, and $1,362, respectively.

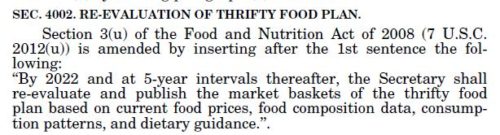

In 2018, the Farm Bill instructed the USDA to re-evaluate the Thrifty Food Plan by 2022 and every five years thereafter. The most recent revisions was in 2006.

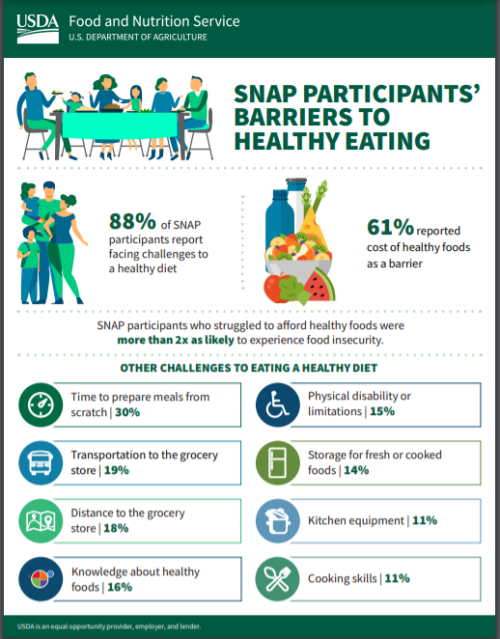

The Thrifty Food Plan has obvious weaknesses:

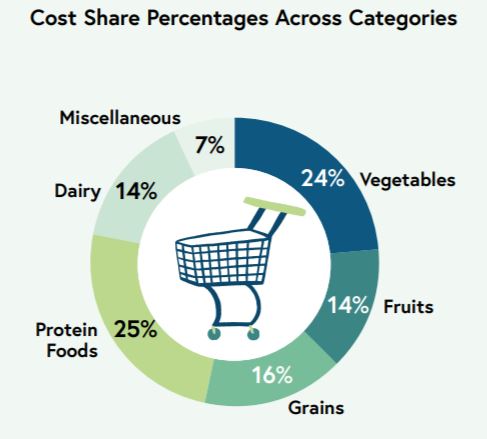

- It is based on unrealistic amounts and kinds of foods.

- The food list is not consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

- It assumes adequate transportation, equipment, time for food preparation.

- It assumes adequate availability and affordability of the listed foods.

- It costs more than SNAP benefits.

The Plan was long overdue for an update. The complaints about process are a cover for the real issue: Republican opposition to raising SNAP costs.

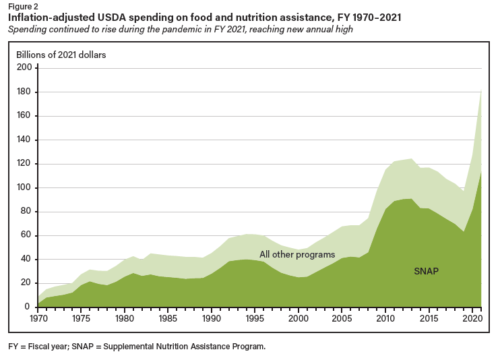

No question, SNAP costs have gone up, and by a lot, in billions.

- 2019 $55.6

- 2020 $74.1

- 2021 $108.5

- 2022 $114.5

Food insecurity has decreased accordingly. And that, after all, is the point.

********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.