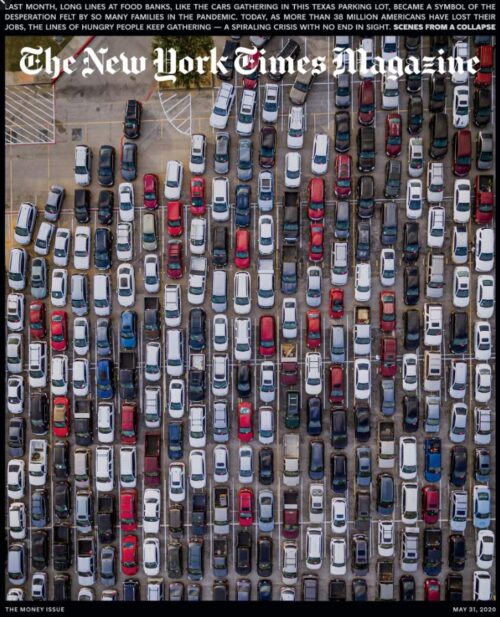

Recent items on food insecurity

With millions of people out of work, food insecurity is becoming a bigger problem than it has been. Some recent items:

From Politico: “Stark racial disparities emerge as families struggle to get enough food”

The last time the government formally measured food insecurity nationally was in 2018. At that time, about 25 percent of Black households with children were food insecure. Today, the rate is about 39 percent, according to the latest analysis by the Northwestern economists, which is set to be published this week. For Hispanic households with kids, the rate was nearly 17 percent in 2018. Today, it is nearly 37 percent.

From Northwestern, a new report: “Food Insecurity During COVID-19 in Households with Children: Results by Racial and Ethnic Groups”

Disparities in food insecurity across racial and ethnic groups are large. Across the eight weeks for which CHHPS microdata are available covering April 23–June 23, 41.1% of Black respondents’ households have experienced food insecurity in the prior week, as have 36.9% of Hispanic respondents’ households and 23.2% of White respondents’ households.

From the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project: “About 14 million children in America are not getting enough to eat”

Accounting for the number of children in these households, I find that 13.9 million children lived in a household characterized by child food insecurity in the third week in June, 5.6 times as many as in all of 2018 (2.5 million) and 2.7 times as many than did at the peak of the Great Recession in 2008 (5.1 million). During the week of June 19-23, 17.9 percent of children in the United States live in a household where an adult reported that the children are not getting enough to eat due to a lack of resources.

From the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: “Boosting SNAP: 5 Reasons Why Households Need More”

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act of March included much-needed measures to temporarily increase SNAP benefits for many households and let state SNAP agencies temporarily modify procedures…But these temporary benefits didn’t help everyone who needs them, and they aren’t enough to help families afford food, given the challenges that COVID-19 and the downturn have presented. Here are five reasons why the next relief package needs to include an additional boost in SNAP benefits:

From The Counter: “Covid-19 has increased online SNAP purchases twentyfold—and Amazon, Walmart have a lock on virtually all those sales”

The USDA has been pushing online food sales for SNAP recipients, and COVID-19 is accelerating the trend. The Counter article explains that

more than 750,000 households had used food stamps benefits online as of late June. That’s up from just 35,000 in March….As of early July, 43 states are approved to accept SNAP benefits online, and 39 have the program up and running.

The Counter also notes:

One thing is certain: At this point, two big retailers stand to benefit from the explosion in online SNAP sales. In 34 of the 39 states, Amazon and Walmart are the only participating grocers. The reasons why are likely logistical.. Few independent grocers have the web infrastructure to display and update their inventory online, making Amazon and Walmart a kind of duopoly by default. Even fewer have enough staff to assemble complex orders and deliver them to people’s homes. By contrast, Amazon and Walmart have been investing heavily in grocery delivery for years.

Comment

No matter how useful they are, online deliveries cost more and SNAP does not pay delivery costs. Online also requires a computer and broadband access. Do SNAP participants have these things?

The 750,000 housaeholds using the online system constitute a small fraction of the 19 million households enrolled in SNAP.

We have a long way to go to solve problems of food insecurity in this country.