Tone deaf food ad of the week: Doritos

Really, I can’t make this stuff up.

I was fascinated to see this article about how offering kids greater amounts and varieties of snack foods encourages them to eat more and, therefore, take in more calories. Snack variety has a greater effect than just larger package sizes (1).

This article immediately reminded me of the infamous cafeteria diet studies of the late 1980s. The investigators fed rats all kinds of junk foods and compared the calories they ate to those eaten by control rats allowed only rat chow. The cafeteria-fed rats ate more (2).

This, of course, is what Kevin Hall and his colleagues found when adults were allowed to eat as much as they wanted of ultraprocessed junk foods (3).

The message is clear: junk food encourages overeating; overeating means taking in more calories; more calories means more weight. Eating a lot of junk food is a sufficient explanation for obesity.

References

I am ever indebted to Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, the Canadian obesity specialist, for keeping a sharp eye out for the more amazing ways food companies push junk foods.

Check out his Weighty Matters blog. This particular post describes the “Smart Snacks” for kids endorsed by the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, founded by the American Heart Association in partnership with the Clinton Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Check out Freedhoff’s selection of “Smart” items drawn from Amazon’s more complete list of Alliance-endorsed items. Here is his first example (but don’t miss the others):

These are all junk foods tweaked to make them slightly less junky, thereby raising the questions I always like to ask in these situations: Is a slightly better-for-you product necessarily a good choice?

I’ve written about the Alliance’s partnerships previously. As Freedhoff explains,

In case you’re not familiar with it, the Alliance For A Healthier Generations is the name given to the partnership program founded between the American Heart Association, The Clinton Foundation, and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation with pretty what at first glance looks like pretty much every food industry corporation on earth…[this] is a partnership with the food industry whose job is to promote sales, not to protect health.

Freedhoff asks:

How is it possible that the American Heart Association, The Clinton Foundation, and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation would describe a child washing down a bag of Doritos or a Pop-Tart with a can of Diet Coke as them consuming a Smart Snack?

The American Heart Association should not be a participant in this Alliance. The “Smart Snacks” program’s endorsement by the Alliance covers these particular products but, by extension, the rest of those companies’ products—and the companies that make them.

Chin Jou. Supersizing Urban America: How Inner Cities Got Fast Food with Government Help. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

I first read this book in manuscript form and have been its biggest fan ever since. It’s terrific that it is now out and can—and should—be read by everyone.

I was delighted to do a back-cover blurb for it:

This page-turner of a book tells a virtually unknown story. Federal policies to assist small businesses deliberately introduced fast-food outlets into low-income minority areas to the benefit of franchise owners but promoting widespread obesity in these communities. For anyone interested in the role of government policy in food, health, and race relations, Supersizing Urban America is a must-read.

I met Chin Jou last year when I was at the University of Sydney, where she now teaches. They are so lucky to have her there. This is first-rate work–a model of how to make historical research totally relevant to today’s food issues.

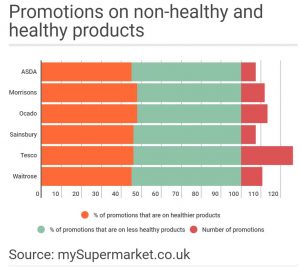

In Great Britain, at least, supermarkets promote junk foods more than they promote healthy foods.

No surprise. Junk foods are more profitable!

Here is the online version of my commentary in New Scientist, March 14, 2015:24-25.

I submitted an illustration with it, which the editors did not use. It’s from the Ontario Medical Association.

Cigarettes get plain packets – will junk food be next?

The tobacco industry is fighting moves to sell cigarettes in plain packs by claiming food manufacturers will be hit next. Will they?

ANTI-SMOKING advocates will be delighted. MPs have today voted in favour of introducing uniform packaging for cigarettes in the UK. That plain wrappers will undoubtedly further reduce smoking, especially among young people, is best confirmed by the tobacco industry’s vast opposition to this government measure and positive evidence from Australia, the first country to adopt it.

Along with lobbying and appeals to the World Trade Organization, the tobacco industry, when under attack, inevitably wheels out well-worn arguments about the nanny state, personal freedom, lack of scientific substantiation, and losses in jobs and tax revenues.

So to perk up its tired and thoroughly discredited campaign, the tobacco folks have added a new argument. Requiring plain wrappers on cigarettes, they say, is a slippery slope: next will be alcohol, sugary drinks and fast food. This argument immediately raises questions. Is it serious or just a red herring? Should the public health community lobby for plain wrappers to promote healthier food choices, or just dismiss it as another tobacco industry scare tactic?

Let me state from the outset that foods cannot be subject to the same level of regulatory intervention as cigarettes. The public health objective for tobacco is to end its use. So for cigarettes the rationale for plain wrappers is well established. Company logos, attractive images, descriptive statements, package colours and key words all promote purchases. Plain wrappers discourage buying, especially along with other measures such as bans on advertising, smoke-free policies, taxes and health warnings.

Australia’s pioneering law specified precise details of pack design, warning images and statements. The result: cigarette brands all look much alike. Most reports say plain packaging boosts negative perceptions of cigarettes among smokers and increases their desire to quit. Australia expects plain packaging to further reduce its smoking rate, which, at 12.8 per cent, is already among the world’s lowest. Along with the UK, New Zealand and Ireland are well on the way to adding plain packaging to their anti-smoking arsenal. More nations are considering it.

Which is all bad news for the tobacco industry. So it ramps up the slippery slope argument, hoping the food industry will support its fight against plain wrappers. It cites examples such as the regulation of infant formula in South Africa, where pictures of babies on labels are forbidden; that’s a big problem for the Gerber food brand – Gerber’s company logo is a smiling baby.

But those peddling the slippery slope idea ignore the fact that the health message for tobacco is simple: stop smoking. But beyond tobacco, it is more complex. For alcohol it is a little more nuanced: drink moderately, if at all. For food it is much more nuanced. Food is not optional; we must eat to live. Nutritional quality varies widely. Foods are spread across a spectrum from unhealthy to healthy, from soft drinks (no nutrients) to carrots or fish (many nutrients). Most fall somewhere in between. What’s more, an occasional soft drink is fine; daily guzzling is not. So the advice is to choose the healthy and avoid or eat less junk, both in the context of calorie intake and expenditure.

Is there any evidence that plain packaging for unhealthy foods would reduce demand? Research has focused on marketing’s effect on children’s food preferences, demands and consumption. Brands and packages sell foods and drinks, and even very young children recognise and desire popular brands. When researchers compare the responses of children to the same foods wrapped in plain paper or in wrappers with company logos, bright colours or cartoon characters, kids invariably prefer the more exciting packaging.

But the problem is deciding which foods and beverages might call for plain wrappers. For anything but soft drinks and confectionery, the decisions look too vexing. Rather than having to deal with such difficulties, health advocates prefer to focus on interventions that are easier to justify – scientifically and politically.

We know that some regulations and market interventions –analogous to, if not the same as those aimed at smoking cessation – are essential for reducing the damage from harmful products. If not plain packaging, then what? Studies suggest small benefits from a long list of interventions such as taxes, caps on portion size, front-of-package traffic-light labels, nutrition standards for school meals, advertising restrictions, and elimination of toys from fast food meals and cartoons from packaging. Rather than dealing with the impossible politics of plain wrappers on foods, health advocates increasingly favour warning labels.

These first appeared on cigarette packs in the 1960s and have been considered for food products since the early 1990s. Heart disease researchers suggested that foods high in calories and fat should display labels such as: “The fat content of this food may contribute to heart disease.” More recently, health advocates in California and New York proposed warning labels on sugary drinks. The Ontario Medical Association takes a similar view: “To stop the obesity crisis, governments must apply the lessons learned from successful anti-tobacco campaigns.” It has mocked up examples of warnings on foods.

Although no warning label law has passed so far, such messages are the logical next step in promoting healthy food choices, in the same way that plain wrappers are the next logical step for all cigarette packages. Health advocates should recognise the slippery slope argument for the typical tobacco ploy that it is.

The New York Times Room for Debate blog asked me to comment on What other unhealthy products should CVS stop selling?

Here’s my response: Next, Cut the Soda and Junk Food.

Good for CVS! Cigarettes are in a class by themselves. The evidence that links cigarette smoking to lung cancer and other serious health problems is overwhelming, unambiguous and incontrovertible. So is the evidence that the mere presence of cigarettes is sufficient to create demand, especially among young people.

When the anti-cigarette smoking movement began, the issues were simple: stop people from starting to smoke and get people who smoked to stop — by making it difficult, uncomfortable and expensive for smokers to continue their habit. The ultimate goal? Put cigarette companies out of business. This, of course, has been politically impossible, not least because cigarette companies pay such high taxes.

If CVS wants to promote health, it could increase sales of healthy snacks, and stop selling sugary foods and drinks.

Although there are many parallels in company marketing practices, food is not tobacco. For all tobacco products, the response is simple: stop. Food is more complicated. We must eat to survive. A great number of foods meet nutritional needs. The evidence that links a particular food product to health is often uncertain. This is because each food is only one component of a diet that contains many foods in a lifestyle that might involve other factors that affect health: activity, alcohol, drugs, stress and let’s not forget genetics.

With that said, if CVS really wants to promote health, it could consider increasing its sales of fruits, vegetables and healthy snacks, and stop selling sodas, ice cream, chips and other junk foods. Those foods may not have the same bad effect on health as tobacco, but eating too much of them on a regular basis is associated with weight gain, obesity and the conditions for which obesity is a risk factor, like Type 2 diabetes and heart disease. If CVS wants to counter obesity, dropping soft drinks is a good place to start. They have scads of sugars, and kids who drink them regularly take in more calories, are fatter and have worse diets than kids who do not.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly the American Dietetic Association) has just concluded its annual meeting and exhibition.

I was unable to attend but colleagues have been sending photos and giving me products or other objects collected at the exhibition. This exhibition is always worth a look. It typically features displays by food companies (Big Food and small) giving away samples of what I love to call “dietetic junk foods” in order to encourage dietitians to recommend them to clients.

Thanks to my NYU colleague, Lisa Sasson, for alerting me to these entertaining examples.

First: sugar-supplemented Stevia:

Next: The National Confectioners Association has a handy guide to moderate candy consumption:

Then: Frito-Lay (owned by PepsiCo) ‘s new Gluten-Free chips.

Potato chips did not ever contain gluten, but never mind. They remind me of products offered during the low-carb craze a few years ago, like the ones I photographed when working on What to Eat in 2005.

Eat healthfully and enjoy the weekend!