Are organic foods more nutritious? And is this the right question?

I received a press release last week announcing the release of a new meta-analysis of more than 300 studies comparing organically produced foods to those produced conventionally. The results show that organic foods have:

- Less pesticides: this is to be expected as they are not used in organic production.

- Less cadmium: this also is to be expected as sewage sludge, a probable source of cadmium, is not permitted in organic production.

- More antioxidants: this is news because some previous studies did not find higher levels of nutrients in organic foods.

I was interviewed by the New York Times about this study:

Even with the differences and the indications that some antioxidants are beneficial, nutrition experts said the “So what?” question had yet to be answered.

“After that, everything is speculative,” said Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University. “It’s a really hard question to answer.”

Dr. Nestle said she buys organic foods, because she believes they are better for the environment and wants to avoid pesticides. “If they are also more nutritious, that’s a bonus,” she said. “How significant a bonus? Hard to say.”

She continued: “There is no reason to think that organic foods would be less nutritious than conventional industrial crops. Some studies in the past have found them to have more of some nutrients. Other studies have not. This one looked at more studies and has better statistics.”

Two additional comments:

1. The study is not independently funded. One of the funders is identified as the Sheepdrove Trust, which funds research in support of organic and sustainable farming.

This study is another example of how the outcome of sponsored research invariably favors the sponsor’s interests. The paper says “the Trust had no influence on the design and management of the research project and the preparation of publications from the project,” but that’s exactly what studies funded by Coca-Cola say. It’s an amazing coincidence how the results of sponsored studies almost invariably favor the sponsor’s interests. And that’s true of results I like just as it is of results that I don’t like.

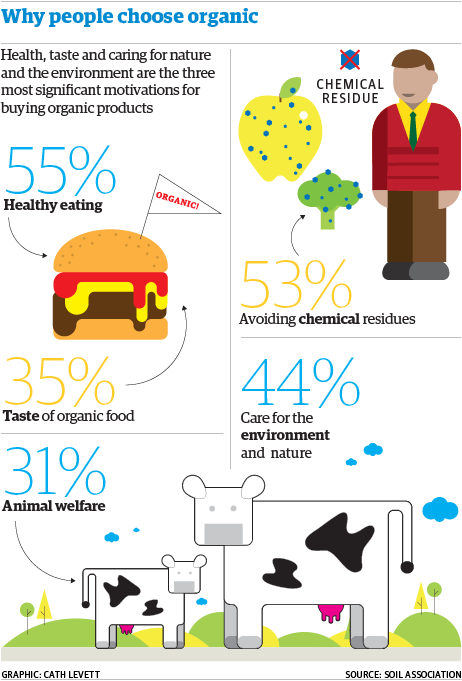

2. The purpose of the study is questionable. The rationale for the study is “Demand for organic foods is partially driven by consumers’ perceptions that they are more nutritious.” The implication here is that research must prove organics more nutritious in order to market them. But most people who buy organics do so because they understand that organics are about production values. As I said, if they are more nutritious, it’s a bonus, but there are plenty of other good reasons to prefer them.

Other resources:

- Supplementary data from the study

- Q and A on the study

- Washington State University press release

- The Guardian story that broke the embargo [nobody was supposed to write about it until July 15]

- The Organic Trade Association’s statement

Christie Wilcox, blogger, Scientific American

Christie Wilcox, blogger, Scientific American Raj Patel, Institute for Food and Development Policy

Raj Patel, Institute for Food and Development Policy Bjorn Lomborg, Copenhagen Consensus Center

Bjorn Lomborg, Copenhagen Consensus Center Tom Philpott, Maverick Farms

Tom Philpott, Maverick Farms