The Washington Post reported yesterday that the FDA is about to launch an initiative to get food companies to reduce the amount of sodium in their foods.

If true, this would be a major big deal. But by late afternoon, the FDA had issued a press release denying the Washington Post’s report (and see note below):

A story in today’s Washington Post leaves a mistaken impression that the FDA has begun the process of regulating the amount of sodium in foods. The FDA is not currently working on regulations nor has it made a decision to regulate sodium content in foods at this time.

Over the coming weeks, the FDA will more thoroughly review the recommendations of the IOM report and build plans for how the FDA can continue to work with other federal agencies, public health and consumer groups, and the food industry to support the reduction of sodium levels in the food supply.

The FDA is referring to a report also issued yesterday by the Institute of Medicine: Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. According to the IOM Summary, voluntary efforts by the food industry to reduce sodium intake have failed. The report’s first recommendation is for the government to set standards for the sodium content of packaged foods. And that sounds like what the Washington Post thought the FDA was about to do.

The idea is to get all companies to start reducing sodium. USA Today quotes Jane Henney, the previous FDA Commissioner who chaired the IOM committee: “The best way to accomplish this is to provide companies the level playing field they need so they are able to work across the board to reduce salt in the food supply.”

The IOM is doing a public briefing on the report at 10:00 a.m. today, at the National Press Club in Washington DC. You can listen to it via audio webcast at www.nas.edu.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) first asked the FDA to start regulating salt in processed foods in 1978. Its press release and report, Shaving Salt, Saving Lives, explain why the FDA’s action would be such good news for public health.

Salt is as controversial as any nutrition issue can get. I expect plenty of pushback from the Salt Institute and other industry trade groups if there is any hint that FDA might be about to regulate salt content. Could the FDA’s denial be the result of industry pressure? It would be interesting to find out.

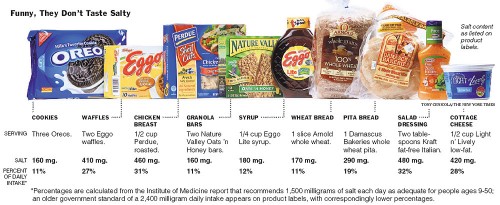

Some basic facts: Recall that sodium is 40% of table salt (sodium chloride). Too much raises the risk of high blood pressure and stroke. Nearly 80% of salt is in processed and pre-prepared foods that are salted before they get to you.

The recommended maximum for adults is 2300 mg or about a teaspoon a day. If you are at risk for high blood pressure, the maximum is just 1500 mg, or two-thirds of a teaspoon. Americans consume more than twice that much on average.

Note added April 20: the FDA has produced a Q and A on its salt regulatory policy.

Additions April 21: Here’s the New York Times story on the IOM report. The LA Times reports on the amounts of sodium in fast food restaurant meals. Impressive.