Should FDA be an independent agency?

A couple of weeks ago, Politico reported that six former commissioners of the FDA agreed that this agency needed to become independent of its present location in government.

The FDA is presently one of eight agencies in the Public Health Service of the Department of Health and Human Services.

The former commisioners think the FDA would be better off having

either Cabinet-level powers or the autonomy of agencies like the Federal Trade Commission or the Securities and Exchange Commission. They argued that the FDA, which regulates more than a quarter of the economy and deals with critical food and drug safety, is harmed by bureaucracy, meddling politicians and confusing budgetary lines in Congress.

Politico quotes former commissioner David Kessler: “The micromanagement from on top has probably gotten to the point where an independent agency is necessary.”

Every decision made by FDA officials must be cleared not only through the FDA bureaucracy, but also through that of HHS—and the White House Office of Management and Budget.

This explains why the FDA appears to—and does—move at pre-climate change glacial speed.

But that’s not the only structural problem that impedes the work of this agency. The other big one is how it gets funded.

The FDA is a public health agency housed in the health department.

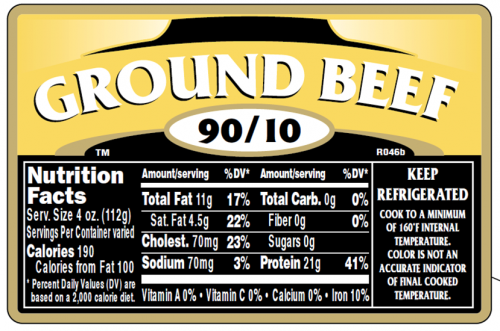

BUT: it gets its congressional funding from House and Senate Agricultural committees.

These can hardly be expected to be sympathetic to the FDA’s regulatory mission to keep foods safe and labeled accurately.

This happened for reasons of history. In its earlier incarnations, the FDA was part of the USDA. It moved, but its funding didn’t.

These calls raise issues about the structure of food regulation at the federal level. I’ve written about calls for a single food agency often on this site. This may be a good time to consider how best to deal with food policy in the next few years. We badly need:

- Food policy linked to health policy

- Better linkage of the FDA’s and the USDA’s food safety regulation

- Better coordination of food and nutrition policy overall

It’s great that the commissioners started this conversation. It’s one well worth continuing.