The new study of protein and weight gain: calories count!

I was intrigued by the new study from the Pennington Research Center concluding that weight gain depends on calories, not how much protein you eat.

The idea that the protein, fat, or carbohydrate content of your diet matters more to weight than how many calories you eat persists despite much evidence to the contrary.

This study did something impressive. It measured what people ate, how much they ate, and how much energy they expended under tightly controlled conditions.

This is unusual. Most studies of weight gain and loss depend on participants’ self reports.

Measuring is much more accurate, as I discuss in my forthcoming book with Malden Nesheim, Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics (out April 1). If you want calorie balance studies to be accurate, you have to measure and control what goes in and out. The Pennington is one of the few laboratories in the country that can do this.

Pennington researchers got 25 brave people to agree to be imprisoned in a metabolic ward for the 12 weeks of the study. The volunteers had to eat nearly 1,000 extra calories a day over and above what they needed to maintain weight. Their diets contained either 5%, 15%, or 25% of calories from protein.

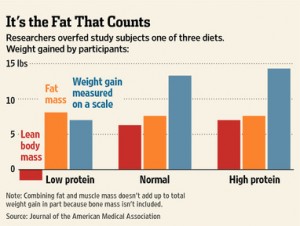

All of the volunteers gained weight (no surprise), although the low-protein group gained the least. Most of the weight ended up as body fat. The medium- and high-protein groups also gained muscle mass. The low-protein group lost muscle mass.

All of the differences in weight gain among individuals could be accounted for by energy expenditure, either as activity or heat (protein causes higher heat losses).

The Wall Street Journal (January 4) did a terrific summary of the results:

This tells you that low-protein diets cause losses in muscle mass (not a good idea), and that there isn’t much difference between diets containing 15% protein (the usual percentage) and higher levels.

The study also suggests that higher protein diets won’t help you lose weight—unless they also help you cut calories. That calories matter most in weight gain and loss is consistent with other studies based on measurements, not estimations.

Of course the quality of the diet also matters: it’s easier to cut calories if you are eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, whole grains and a varied diet based largely on relatively unprocessed foods—and it’s harder to gain weight on such diets.