The new obesity drugs: a threat to the food industry?

I can hardly believe this, and had to laugh when I read all the articles last week about how worried the food industry is about the new obesity drugs.

Imagine: if the drugs really do reduce appetite and interest in food—horror of horrors—people might eat less.

Eating less, as I have pointed out repeatedly, is very bad for the food business.

In Food Politics, I explained how the fundamental purpose of food companies is to get you to eat more food, not less.

Beginning in the early 1980s, food companies did a better job of creating an “eat more” food environment.

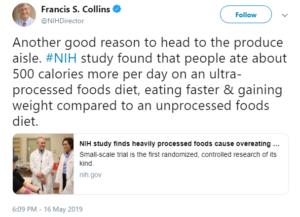

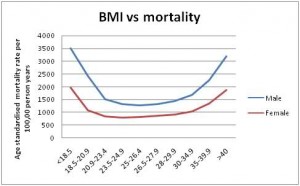

People responded to this environment by eating more calories—lots more—and way more than enough to account for the rising prevalence of overweight and obesity. Evidence? See my book with Mal Nesheim, Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics.

When I am at my most cynical, I ask this question: What industry might benefit if people ate more healthfully?

I am hard pressed to think of any—certainly not the food, diet, or diet-drug industries (Novo Nordisk, maker of the semaglutide drug, Wegovy, now makes more than the gross domestic product of Denmark).

The only exception I can think of is not-for-profit HMO’s like Kaiser Permanente, which do better if their patients are healthier (and have no excuse for not paying their workers better).

Anything that helps people eat less and more healthfully is bad news for the food industry, and especially for companies making ultra-processed junk food.

No wonder companies are worried.

Here’s my collection from last week (with thanks to Lisa Young and Michele Simon for making sure I saw these articles):

- Wall Street Journal: America’s Food Giants Confront the Ozempic Era

- Yahoo Finance: Ozempic Is Making People Buy Less Food, Walmart Says

- Bloomberg News: If Ozempic Leads People to Eat Less, Maker of Cheez-It Will Be Ready

- Yahoo Finance: Snack-maker Conagra may tweak portions as weight-loss drugs alter appetites

- Washington Post: Food, clothing, airlines: Ozempic is coming for these industries and more

- Yahoo Finance: Surge in obesity drugs like Ozempic has pummeled big food stocks. Is it time to eat them up?

- Food Fix: Why Ozempic makes Wall Street woozy

- PepsiCo: PepsiCo monitoring impact of weight loss drugs, but says early impact on sales is ‘negligible’