Who knew? I. Bribery in food supply chains

This week, I’m posting some items that surprised me. Here’s the first: How to deal with bribery in your supply chain.

Really? This is an international problem? Apparently so, at least for the U.K.

We have approximately 160 coudntries from all over the world contributing to our food supply and this can lead to vulnerabilities in respect of fraud and financial crime.

The vulnerabilities:

- Bribery and corruption

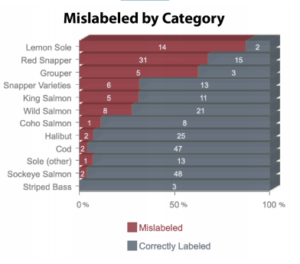

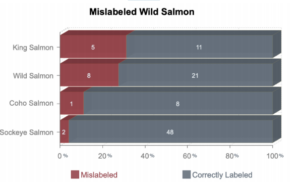

- Food fraud such as adulteration and mislabeling

- Dealing with entities on international fraud and sanction lists

- “Dealing with individuals or entities that do not share your own approach to issues such as sustainability and modern slavery.”

This particular article deals with bribery. A few excerpts from this discussion:

- It is not necessary to show the payment was made with a corrupt motive or intention to persuade or influence the agent; the payment is presumed to have been corrupt if the principal was unaware.

- There is also no need to show the principal suffered a loss as a result of the agent being bribed.

- Given the serious consequences which can flow from bribery (corporate criminal conviction, fines, reputational damage) and the cost of carrying out your own investigation, prevention is clearly better than cure.

- In the food industry, supply chains can be particularly long and complex, with suppliers involved from all over the world; therefore, it is crucial that businesses invest time in getting to know their suppliers.

- The key message is to keep the risk of bribery in mind at all stages of dealing with suppliers and ensure that all counterparties are aware of your organisation’s understanding of how the civil law of bribery can protect and help scrutinise suppliers, so to maintain a robust supply chain with in-built deterrents for rogue parties.

One more thing to worry about if you are in the food business.