This session is on Practicing Food Studies. It will be at 5;00 p.m. Details to come.

Health claims: Should the First Amendment protect bad science?

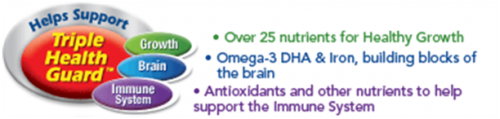

I keep complaining about the health claims on Enfagrow toddler formula, a sugary product aimed at children from ages one to three:

These claims, for the uninitiated, are a special kind called structure-function. Congress authorized such claims when it passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) in 1994.

Structure-function claims do not say that the product can prevent or treat disease. They merely suggest that the product can help in some unspecified way with some structure or function of the body.

When Congress passed DSHEA, it meant the claims to apply to dietary supplements, not foods. Enfagrow is marketed as a food, not a supplement. It displays a Nutrition Facts label, not a Supplement Facts label.

Over the years, the FDA has issued cease-and-desist warnings about foods that bear structure-function claims. In recent years, it has simply stated that manufacturers are responsible for ensuring that the claims are “truthful and not misleading.”

One reason for the shift is what the Courts have ruled. The Courts say that structure-function claims are protected by First Amendment guarantees of free speech. The most recent case is Alliance for Natural Health USA v. Sebelius. As described in Food Chemical News (June 7), a D.C. District Court judge ruled that the FDA cannot deny health claims that link selenium supplements to reduced risk of several diseases, or require those claims to be qualified, just because the claims lack adequate scientific substantiation.

In other words, supplement makers can say anything they want to about the benefits of their products—on the grounds of free commercial speech—whether or not science backs up the claim.

Recently, the FDA issued a warning letter to Nestlé, the maker of a Juicy Juice product aimed at toddlers, which displays a claim that its content of added omega-3 DHA improves brain development. The FDA did not take on the claim, even though research seems unlikely to find that such drinks have any special benefits for brain development. Instead, the FDA focused on a technicality:

The product makes claims such as “no sugar added,” which are not allowed on products intended for children under 2 yrs of age because appropriate dietary levels have not been established for children in this age range.

I’m guessing—this is speculation—that the FDA is reluctant to take on Enfagrow’s brain or immunity claims because Mead-Johnson has deep pockets and might well be willing to fight this one in court as a First Amendment case.

I am not a lawyer but I thought that intent mattered in legal cases. Surely, the intent of the founding fathers in creating the First Amendment was to protect the right of individual citizens to speak freely about their political and religious beliefs. Surely, their intent had nothing to do with protecting the rights of supplement, food, and drug corporations to claim benefits for unproven remedies, or to promote sales of sugary foods to babies.

I think it is time to give these First Amendment issues some serious thought. How about:

- FDA: Fire those lawyers and hire some who will protect the FDA’s ability to use science in its decisions.

- FTC: Take a look a the immunity claim on the Enfagrow Vanilla toddler formula, now that the Chocolate is off the market.

- Legal scholars: Surely there are ways to protect real First Amendment rights while restricting unsubstantiated health claims?

Other ideas are most welcome. Your thoughts?