This article appeared yesterday in the Datebook section. The dogs loved the food—a huge relief because we had not tested the recipes (oops).

Photos by Russell Yip. Aussies borrowed.

Challenging the pet-food dogma

Meredith May, San Francisco Chronicle, June 23, 2010

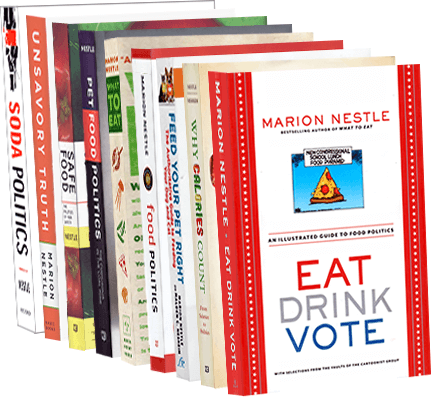

In her best-selling food industry exposés “What to Eat” and “Food Politics,” Marion Nestle taught the nation how to shop smarter at the supermarket. Now the New York University nutrition professor and Chronicle Food Matters columnist has teamed with animal nutrition expert Malden C. Nesheim to examine the $18 billion pet food industry in “Feed Your Pet Right: The Authoritative Guide to Feeding Your Dog and Cat” (Simon & Schuster; $16.99).

Their research-based work examines the politics, marketing and science behind pet food, and offers pet owners advice on how best to feed America’s 172 million cats and dogs. She recently visited The Chronicle’s test kitchen, where canine tasters wolfed down an easy-to-prepare recipe from the book.

Q: This book began when you couldn’t understand the ingredients on pet food labels?

A: I couldn’t! I was in a supermarket in Ithaca (N.Y.), and the pet food aisle was 120 feet long. I was stunned by the amount of real estate devoted to it. This had to be some huge industry, and it surprised me because I didn’t think dogs and cats had taken over the world. I looked at the label and it didn’t make any sense at all: stuff about guaranteed analysis, profiles and health claims all over it. We gathered all the books we could find on feeding pets, and they were so dogmatic – saying you have to feed your pet this one way and everything else was poison. They were enormously contradictory, and none seemed to be based on actual research.

Q: Is it in the best interest of the pet food industry to confuse us?

A: Of course – they are selling products that are inexpensive to make and profitable to sell, and all they have to do is convince pet owners if they don’t use their products, they are making a big mistake.

They would prefer you don’t think about what’s in there – the byproducts of human food products. There are billions of pounds of leftover parts of cows, pigs, chickens and sheep after they are slaughtered for human consumption, and something has to be done with it or it will be wasted. One way is to feed it to dogs and cats. They don’t care what part of the animal it comes from.

Q: Give us a cheat sheet. What should we look for on the label?

A: If you want one-stop shopping that meets all the nutritional needs of your cat or dog, look for the words “complete and balanced” on the package. That’s code for meeting all the nutritional standards set by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) – the non-regulatory agency that sets the pet food standards.

Next is the ingredient list. Our rule of thumb is to check the first five ingredients; after that, the ingredients are so small, they do not amount to much. The first five should be real foods – not wheat gluten or something that doesn’t sound like real food. A lot have meat byproducts in them that are quite nutritious, but a lot of people think they are disgusting.

Beyond that, if you are concerned about the quality and interested in organic, seasonal and locally grown, you can find a commercial pet food that meets those standards, but typically you will pay more.

Q: Is there some truth to the claims that some foods are for aging pets, puppies, weight loss, organic, premium?

A: You can pretty much trust it the way you can human food labeling. There will be cheats every now and then.

Q: Is price an indicator of quality?

A: We were rather surprised by what we found. We bought a collection of chicken dinners for pets that were all premium brands, which is a code for higher price. We compared the first five ingredients, the health claims and price, and although the ingredients were all the same, there was a threefold increase in price. So there’s some heavy marketing going on here. The word “premium” has no regulatory meaning, so you have to read what’s in the product.

Q: What are the main things we are doing wrong when it comes to feeding our pets?

A: Overfeeding.

Q: Should we just be cooking for our pets?

A: People who do say it is healthier. One of the funniest things we found was a big clinical research book for cats and dogs put out by Hills Co. that had a very long chapter about how dangerous it is to cook for your pets, then it gave generic recipes for cat and dog food that were easy to follow. We put the recipes in our book!

Q: Since the invention of commercial pet food, is there any evidence that pets are healthier or living longer? Or the opposite?

A: We were curious what did people do before commercial pet food. But there was little information and an astonishing lack of research about pet life spans. In the last 10 years, there’s been some preliminary evidence that life spans of dogs and cats have increased a little bit, but I wouldn’t want to push that too hard. There’s certainly evidence that pets are not doing any worse since commercial pet food was invented.

Q: The top five pet food companies control 80 percent of the market – who is regulating them?

A: All of those five companies are also either human food companies or consumer product companies. Governing them is a complicated regulatory system comprised of the (Food and Drug Administration’s) Center for Veterinary Medicine, AAFCO and states. States have their own rules, AAFCO sets models it wishes all states would follow but about half do, and the FDA regulation is minimal. But that’s changing.

Q: Is that because of the pet food recalls in 2007 that were traced to melamine in China?

A: Yes, it made everyone realize we only have one food supply – and it feeds humans, pets and farm animals. If we have a problem with pet food, then there will likely be a problem with all food. Sure enough, melamine showed up in baby formula in China and in a lot of products that were supposed to be containing milk. We need a food-safety system covering the whole thing, and the FDA is not unsympathetic to that approach. We need food labels on pet food that we can read, and calorie counts should be on them.

Q: What foods are deadly to pets?

A: Raisins, grapes or macadamia nuts, onions, garlic and chocolate. Little amounts really won’t do any harm; it’s pounds that causes problems.

Q: If you want to cook for your pet, how do you do it properly?

A: Follow a recipe.

Q: On your book tour, what are the most common questions people have?

A: A lot of questions about poop and how to keep the amount down – all these people in Manhattan apartments want to know. I tell them feed a high-premium, low-residue product with not much fiber in it. PetCo even has a sign showing the poop size comparisons using these kinds of products.

Recipes: Homemade food that gives pets the nutrition they need. E5

Homemade Dog Food

From “Feed Your Pet Right,” by Marion Nestle and Malden C. Nesheim (Simon and Schuster; $16.99). This recipe, adapted from guidelines in “Small Animal Clinical Nutrition” (2000), feeds one 40-pound dog. Amounts should be adjusted to the size, age and condition of the animal.

- 8 ounces cooked grains (rice, cornmeal, oatmeal, pasta and other grains and cereals)

- 4 ounces cooked meat (beef, lamb, pork, chicken, turkey, fish)

- 2 teaspoons fat (beef fat, chicken fat, vegetable oil, olive oil, fish oil)

- 1 ounce raw or cooked vegetables

- 1 teaspoon bone meal (or dicalcium phosphate supplement, see Note)

- 1/4 teaspoon potassium chloride supplement (salt substitute)

- 1 human adult daily multi-vitamin, multi-mineral tablet

Instructions: Combine the ingredients in a bowl. Mix well and serve.