Smart Choices: 44% sugar calories!

You may recall my previous posts about the new Smart Choices program. This program was developed by food processors to identify products that are ostensibly “better for you” because they supposedly contain more good nutrients and fewer bad ones. This program is about marketing processed foods and I wouldn’t ordinarily take it seriously except that several nutrition professional associations are involved in this program and the American Society of Nutrition is managing it. In effect, this means that nutritionists are endorsing products that bear the Smart Choices logo.

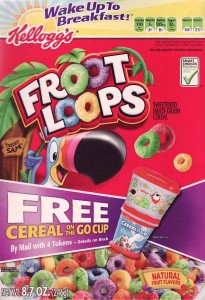

So what products are nutritionists endorsing? I went grocery shopping last week and bought my first Smart Choice product: Froot Loops!

Froot Loops

Look for the check mark in the upper right of the package. Frosted Flakes also qualifies for this logo, and do take a look at what else is on the approved list.

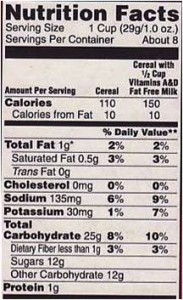

A close look a the Nutrition Facts label of Froot Loops shows that it has 12 grams of added sugars in a 110-calorie serving. That’s 44% of the calories (12 times 4 calories per gram divided by 110). The usual program maximum for sugar is 25% of calories but it makes an exception for sugary breakfast cereals. Note that the fiber content is less than one gram per serving, which makes this an especially low-fiber cereal.

OK. I understand that companies want to market their processed foods, but I cannot understand why nutrition societies thought it would be a good idea to get involved with this marketing scheme. It isn’t. The American Society of Nutrition gets paid to manage this program. It should not be doing this.

OK. I understand that companies want to market their processed foods, but I cannot understand why nutrition societies thought it would be a good idea to get involved with this marketing scheme. It isn’t. The American Society of Nutrition gets paid to manage this program. It should not be doing this.

But, you may well ask, where is the FDA in regulating what goes on package labels?

Good news: I am happy to report that our new FDA is on the job! FDA officials have written a letter to the manager of the program. Although the letter is worded gently, I interpret its language as putting the program on high alert:

FDA and FSIS would be concerned if any FOP [Front of Package] labeling systems used criteria that were not stringent enough to protect consumers against misleading claims; were inconsistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans; or had the effect of encouraging consumers to choose highly processed foods and refined grains instead of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains [my emphasis].

Update August 25: I received an interesting e-mail message from a member of the Keystone group that developed the Smart Choices program. The message confirms that this program is a scheme to make junk foods look healthy. It says:

Glad to see your posting about Froot Loops! The negotiations over criteria were interesting. Lots of good debate on various points, but when the companies put their foot down, that was it; end of discussion. And sugar in cereals was one such point. Others included the non-necessity for breads, etc. to contain half or more whole grains and the acceptance of fortification to meet the nutrient requirement.

In other words, some people in the group argued that breads needed to contain at least half a serving of whole grains to quality and that added vitamins and minerals should not count toward qualification. Too bad for them. I guess the companies put down feet. But why didn’t they speak up then? And why aren’t they speaking up now?