USDA’s food boxes: some feedback

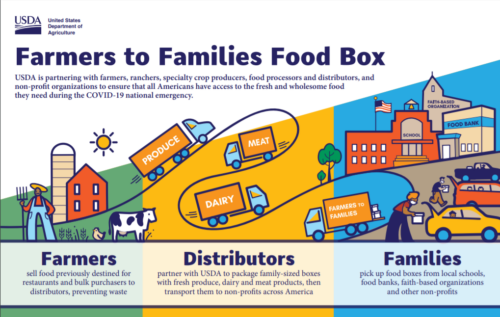

Last week, I asked readers to tell me how the USDA’s Farmers to Families food box program looked on the ground. I got a bunch of responses, but let me start with Andrew Coe’s op-ed in the New York Times, or, as he wrote me, his rant titled: “Free produce, with a side of shaming.”

The subheading: “Instead of beefing up the SNAP program during the pandemic, the government opts for a return to Depression-era food lines.”

The goal of the people on these lines? “A food pantry that has cardboard containers stacked on the sidewalk in front.”

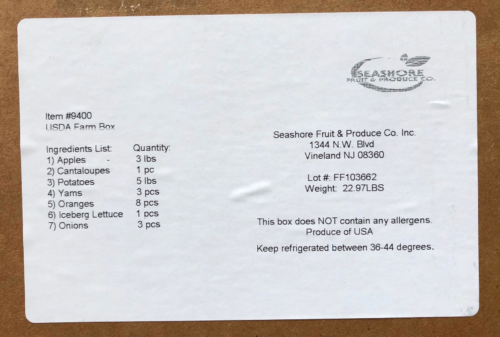

These are “U.S.D.A. Farmers to Families Food Boxes,” each holding 23 pounds of produce: apples, cantaloupes, potatoes, yams, oranges, iceberg lettuce, onions. When the men and women at last get to the front of the line, they are given one of these boxes to put in their shopping carts and take home. This food is supposed to help tide them over until they get a job, or until the next week, when they can line up again on the same sidewalk.

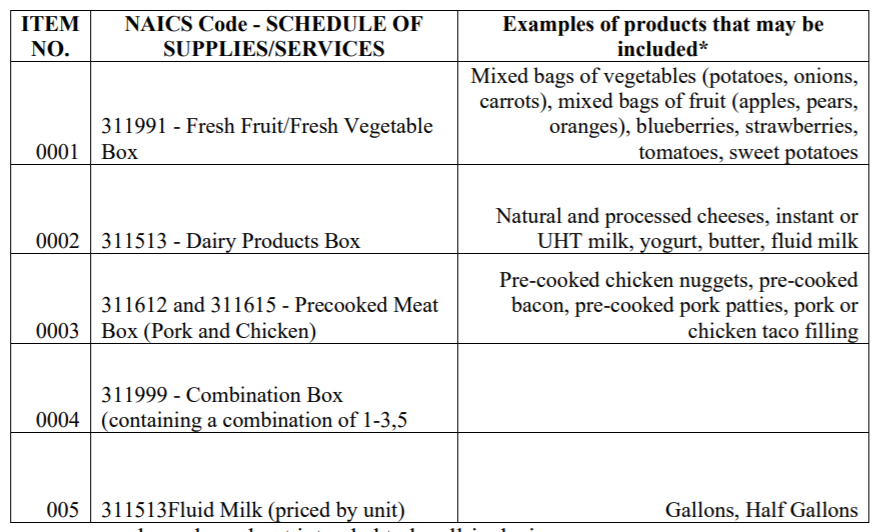

OK. So my questions about this emergency—and highly unsustainable method for achieving the program’s concurrent goals, feeding the hungry and buying from farmers who don’t have any way to sell their products–are (1) is it providing decent food to those who need it, and (2) is it helping farmers who need help.

My correspondents provided some answers, although not enough to really know what is going on.

Two people sent me box labels:

One reader referred me to Instagram photos from #farmerstofamiliesfoodbox, and a Vermont public radio discussion of the boxes.

Another Vermont reader said that “The main contract was landed by a well-regarded local food service company – with the initial support of our agency of ag folks – and they’ve worked very closely with a number of other state, private and nonprofit groups to get a fair bit of regional and Vermont products – especially dairy – in the boxes.” She referred me to an article about the program with this photo of a box with local dairy.

A California reader who works at a food bank said:

We had tons of food that volunteers bagged up individually. One big bag would get eggs, celery, potatoes, apples, nectarines, tangerines, and 1-2 bread products. When cars came to pick up their food, in addition to the bag above, which often had more than what’s noted there, they got a “regular” veggie farm box from Farm Fresh to You, a local CSA. It was all packed up and ready to go, delivered by a truck on a pallet.

I received a lengthy explanation from a food sourcing coordinator at a food bank in Colorado. Here are some of her comments:

- We’ve seen our distribution increase by 40% since March.

- We secured a partnership with a large produce distributor in Missouri for produce boxes, and a regional milk distributor in Colorado. Deliveries from these vendors began on May 20.

- They’ve addressed issues with box size, transportation and pallet structural issues, and cancelling loads or adding additional deliveries as we requested.

- We are receiving 3.2 million pounds of CFAP product each month from these vendors, in the amounts and delivery schedule that we requested. This is a 50% increase over our pre-COVID monthly distribution numbers.

She talked about the problems they were having:

There was definitely a lot of confusion, miscommunication, and misinformation given to both food banks and the distributors by USDA. The program was touted to the food banks as being “truck to trunk”, with distributors delivering directly to distribution sites. However, after the vendors were awarded, the vast majority indicated that they…only had the capacity) to deliver to food bank warehouses with commercial dock doors and large amounts of storage.

When food banks attempted to push back and request funding from USDA or distributors in order to cover the substantial costs to them that this model would incur, the USDA told distributors that they could not subcontract with us. One vendor said that these requests amounted to “extortion” by food banks. [Our] Food Bank…ended up having to secure an additional warehouse, hire 5 staff, and rent 8 new vehicles in order to handle the amount of product we are receiving. The cost to us is about $100,000/month in order to take on the additional product. None of that cost is reimbursed by USDA, which is reimbursing the entire costs of procurement, packaging, and transportation for the distributors. Here’s a link to an article about those additional costs…. we’re fairly unique among food banks in being able and willing to incur those additional costs.

She sent a photo of what’s in the boxes, judging the quality as very high.

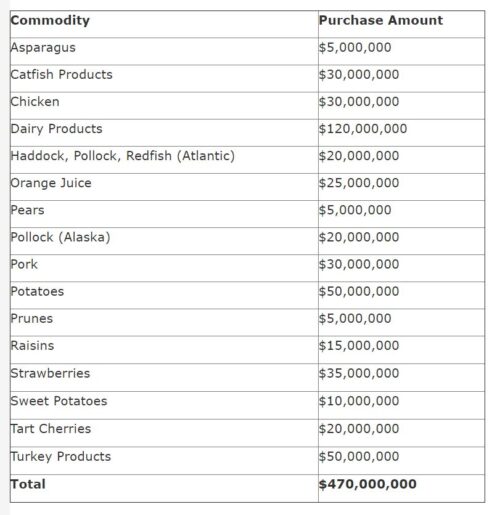

Does the program benefit small producers?

- The milk distributor is a local company.

- The onions and potatoes are also sourced from Colorado growers…[but] the Colorado growing season doesn’t kick into full gear until late June.

- Our meat is coming out of Wisconsin…subcontracted with another distributor…so I don’t know where that meat comes from.

- Many of our small farms who originally submitted bids for the program and were not awarded have not been included in produce sourcing by the distributors that were awarded.

Her conclusion: “While CFAP has definitely been a big lift for us to get up and running, and has had many stumbling blocks since its inception, the enormous amount of high-quality, very in-demand product that we’ve been able to distribute to our clients across Colorado and Wyoming has, in my mind, made the program a success for us.”

OK, so the program is working, as far as it goes, but at great cost. I’m with Andy Coe on this one. This is helping distributors more than farmers, and is demeaning to recipients. There are much better ways to solve both problems. If only we had the political will to take it on.

Addition

Jerry Hagstrom, of The Hagstrom Report, to which I faithfully subscribe, writes:

I don’t see any of your readers making the following points:

- The object of the box program was to find a way to make use of the foods–particularly fruits and vegetables but also pork, chicken and dairy– that were intended for restaurant and institutional use, much of which would spoil if a quick way was not found to use it. Increasing SNAP benefits would not address the problem of figuring out how to distribute food that was intended for restaurants and institutions. As I understand it many of the farmers and distributors engaged in that business do not have any relationship with grocery store distributional channels.

- The SNAP program requires applications and documentation before someone is approved for the program. That takes time. The box program has moved food fairly quickly.

- As far as I know, food banks do not ask people if they are low income. So people who are suddenly low income can go there and get food, which they cannot do so quickly through the SNAP program.

- It would seem to me the food box program was a short term solution, although I don’t know what the farmers and distributors that have been selling to the restaurants and institutions are supposed to do if that demand does not return quickly. Should they go out of business or should some system be found to keep them in business until demand picks up? Would that mean continuing the food box program?

These are worth considering. But the real question, it seems to me, is how to develop a food assistance system that helps people who need food in a more efficient way, while helping farmers find outlets for what they produce that guarantee them a decent living. We all need to be working on that.