When the FDA advisory came out a week or so ago, I started getting questions about whether it meant that women must eat fish during pregnancy and, if so, how much.

As I said in my previous post on the topic, if you like fish, of course eat it, otherwise I can’t think of any compelling reason why anyone has to eat fish.

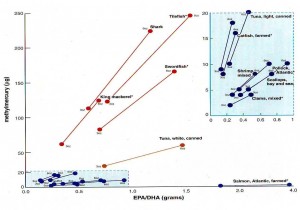

I view the data on the dilemma caused by omega-3 fatty acids in fish (good) versus the content of methylmercury (bad) as still rather uncertain. Dr. Malden Nesheim and I discussed this point in an editorial we wrote for the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition [reference 1 below].

Here’s what the FDA advisory says:

Eat 8 to 12 ounces of a variety of fish each week from choices that are lower in mercury. The nutritional value of fish is important during growth and development before birth, in early infancy for breastfed infants, and in childhood… Fish contains important nutrients for developing fetuses, infants who are breastfed, and young children. Fish provides health benefits for the general public. Many people do not currently eat the recommended amount of fish.

This is a prescriptive statement telling pregnant women that they should eat fish.

I would argue that the data on which FDA based this prescription are limited, especially because the results of its scientific assessment are based mostly on theoretical models rather than empirical studies.

Here’s what makes me think some skepticism is warranted:

- The effects of even low-level methylmercury exposure may be greater than discussed in the assessment [see reference 2], as the latest analysis from the Environmental Working Group explains.

- The increase in young children’s IQ associated with fish-eating during pregnancy is low—-0.7 to a maximum of 3 IQ points.

As the FDA’s assessment report says:

On a population basis, average neurodevelopment in this country is estimated to benefit by nearly 0.7 of an IQ point (95% C.I. of 0.39 – 1.37 IQ points) from maternal consumption of commercial fish. For comparison purposes, the average population-level benefit for early age verbal development is equivalent in size to 1.02 of an IQ point (95% C.I. of 0.44 – 2.01 IQ size equivalence). For a sensitive endpoint as estimated by tests of later age verbal development, the average population-level benefit from fish consumption is estimated to be 1.41 verbal IQ points (0.91, 2.00). The assessment also estimates that a mean maximum improvement of about three IQ points is possible from fish consumption, depending on the types and amounts of fish consumed.

How significant is this? And does the small benefit in childhood persist into adolescence or adulthood?

- The economic question. Fish are expensive.

- The ecological questions. Advice to increase fish consumption comes up against environmental realities—-overfishing, fish farming—-that make the recommendation impossibly unsustainable [reference 3].

- The levels of long-chain omega-3s in farmed fish depend on feeding them wild fish, an ecological problem on its own.

- Guidance about fish can’t be just nutritional; it has to take the economic and ecological impact of fish choices into consideration [reference 4].

- Current per capita fish consumption is about half the FDA recommended level, and half of that is shrimp. Fortunately, shrimp don’t have much mercury (although the ones from Asia may have other contaminants), but they also don’t have much omega-3).

All of this suggests grounds for skepticism. I think a better recommendation would leave more wiggle room to account for uncertainties. Here’s how I would edit the FDA’s statement:

Pregnant women may eat up to 8 to 12 ounces of a variety of fish each week from choices that are lower in mercury. Fish are useful sources of nutrients that may have value for growth and development before birth, in early infancy for breastfed infants, and in childhood, and may provide health benefits for the general public. Other food sources also provide such benefits.

References

[1] Nesheim MC, Nestle M. Advice for fish consumption: challenging dilemmas. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;99:973-974.

[2] Karagas MR, Choi AL, Oken E, Horvat M, Schoeny R, Kamai E, Cowell W, Grandjean P, Korrick S. Evidence on the human health effects of low-level methymercury exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2012; 120:799-806.

[3] Jenkins D, Sievenpiper JL, Pauli D, Sumaila UR, Kendall CWC Are dietary recommendations for use of fish oils sustainable? Canadian Medical Association Journal 2009;180: 633-637.

[4] Oken E, Choi AL Karagas MR, Marien K, Rheinberger CM, Schoeny R, Sunderland E, Korrick S Which fish should I eat? Perspectives influencing fish consumption choices. Environmental Health Perspectives 2012;120:790-798.