Politics, they say, makes strange bedfellows. I can understand why the New York Times would do a front-page investigative report on how soda companies engage minority groups as partners while slamming Mayor Bloomberg for overreaching with his soda cap initiative.

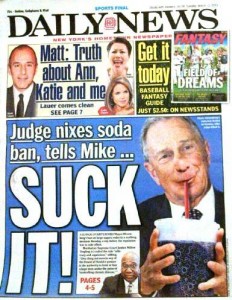

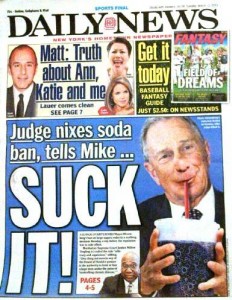

But can someone please explain the Daily News? Here’s yesterday’s front page:

This was followed by two pages of “Soda plan struck down; our cups runneth over” and other gleeful responses to the judge’s soda cap decision.

But then there’s this astonishing editorial. Explain, please.

Judge drinks the Kool-Aid

In putting Mayor Bloomberg’s soda ban on ice, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Milton Tingling did a huge disservice to the health and welfare of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers.

Tingling concluded that the prohibition against selling sugared beverages in containers larger than 16 ounces was both arbitrary and beyond the authority of the Board of Health, which approved the regulations.

The only thing arbitrary here was Tingling’s ruling. More, the judge was the only party who was guilty of overreaching.

At heart, he simply substituted his judgment as to sound public policy for the board’s — an action that’s beyond a judge’s proper purview.

Most amazingly, Tingling held that the board had acted rationally in voting the portion cap as one method of trying to rein in the city’s epidemic of obesity and obesity-related diseases.

He bought the indisputable premise that the board was right to draw connections among high soda consumption, obesity and diabetes, which are debilitating New Yorkers young and old.

But then the judge threw that over by stating the obvious fact that the board did not have the power to ban supersized sugar drinks everywhere, only in establishments regulated by the Health Department.

Because the public could get a 32-ounce cup at, say, a 7-Eleven, but not at restaurants, he in effect deemed the ban to be an ill-designed contraption destined to fail. But who is Milton Tingling to say that? No one.

His fundamental error was to consider the regulation from the point of view of vendors who were hoping to get out from under it.

Those covered by the ban claimed they were the victims of capriciously unequal treatment and shifted Tingling’s concern away from the pressing rationale for a regulation that would have been broadly applied.

There’s nothing arbitrary about the consequences of drinking large quantities of sodas and other overly sweetened beverages.

The correlation in certain communities among consuming soda, becoming obese and contracting related diseases are certain.

The neighborhoods with the highest obesity rates — Harlem, the South Bronx, central Brooklyn — have the largest percentages of people who are likely to drink more than one sugar-sweetened beverage each day.

All too predictably, people in low-income areas such as Bedford-Stuyvesant and East New York, Brooklyn — places where soda consumption is highest — are four times as likely to die from diabetes as residents of the more affluent upper East Side, where people generally consume far fewer sugary drinks.

No matter.

Tingling attended to the arguments of businesses looking after their own financial interests over the demands of public health — while at the same time declaring that the Board of Health is barred from taking into account the substantial economic costs generated by obesity.

Ultimately, Tingling bought into the all-or-nothing argument — the same line of thinking that killed an earlier Bloomberg proposal that would have barred people from buying sugary sodas with food stamps.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture killed that experiment, asserting that it would be unfair and unproductive to target only a limited population in such a test. So Bloomberg tried to go bigger, and Tingling shot him down.

If bringing down a serious threat is a rational goal, as Tingling wrote, then you do it as best you can, even incrementally.

A halfway measure is better than no measure and is certainly not arbitrary.

Bloomberg vows an appeal.

Here’s hoping that Tingling’s judicial superiors recognize that pursuing public health is not just rational, it’s imperative.

Afterthought: compare this to the Times’ editorial:

There are better ways for Mr. Bloomberg to use his time and resources to combat obesity. One is to push Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the State Legislature to impose a penny-per-ounce tax on sugary drinks…the big-drinks ban was ill conceived and poorly constructed from the start.