I’m on record as calling previous Farm Bills “visionless.”

Given what’s happening in Congress, some consider it a bipartisan win? It is, but only because, as the Washington Post put it, the outcome is bad but could have been a lot worse.

The 2018 Farm Bill remains a visionless mess. It continues to favor Big Agriculture and mean-spiritedness over what this country badly needs: a food system explicitly aimed at promoting public health, basic support for the poor, the livelihoods of real farmers and farm workers, and environmental sustainability.

The bill takes up 807 pages, with a table of contents of 11 pages. It will cost taxpayers $867 billion over ten years. That’s more than $1 billion per page.

How to approach the Farm Bill

Start by using the search function to look for key words. These turn up in the Table of Contents, which gives section numbers. Then search by section number. Items dealing with sustainable agriculture and production of food—as opposed to feed or fuel—generally turn up in the Horticulture title. For the rationale behind these decisions, see the Senate’s explanation.

Items of immediate note:

SNAP

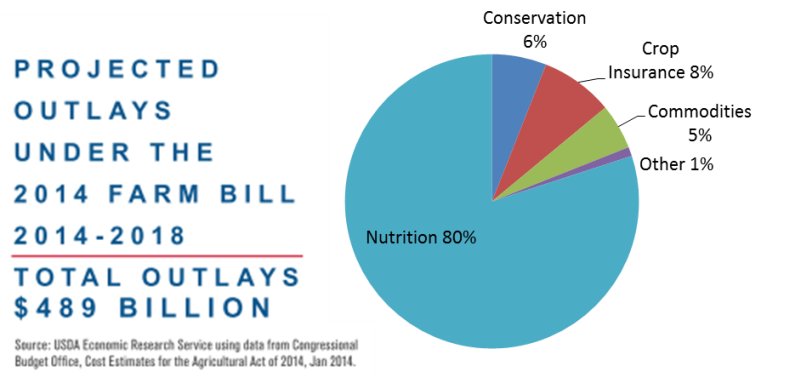

Recall that more than 75% of Farm Bill expenditures go for SNAP—The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly Food Stamps).

The “bipartisan win”? Attempts to cut SNAP expenditures and introduce work requirements failed to pass (whew), although Congress is still working on ways to cut enrollments.

Commodity payments

The bill allows payments to more distant relatives of farm owners—cousins, nieces, nephews—a gift to the already rich. Payments can still go to those earning more than $900,000 a year in adjusted gross income (sigh).

Organics

The bill authorizes $395 million in research funding over the next 10 years, and small amounts for data collection, offset of certification costs, and technology upgrades. But the bill weakens restrictions on chemicals that can be used in organic production.

Hemp

The bill grants $2 million a year for support of hemp as a crop, and authorizes USDA to study the economic viability of its domestic production and sale. It also authorizes Indian tribes (that’s the term the bill uses) to grow hemp.

Cuba

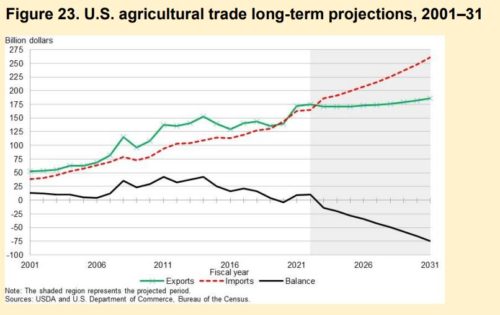

The bill allows funding for USDA trade promotion programs in Cuba.

The Managers recognize that expanding trade with Cuba not only represents an opportunity for American farmers and ranchers, but also a chance to improve engagement with the Cuban people in support of democratic ideas and human rights…The Managers expect that the Secretary will work closely with eligible trade organizations to educate them about allowable activities to improve exports to Cuba under the Market Access and Foreign Market Development Cooperator Programs.

One sweet gift: in memory of Gus Schumacher

The Managers also agree the FINI [Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive] and Produce Prescription should be renamed the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program, in recognition of Mr. Schumacher’s role in the establishment of nutrition incentives nationwide. Mr. Schumacher was a magnificent advocate for farmers and families and saw the importance in building access and affordability through incentive programs.

Commentary

Dan Imhoff’s analysis in Civil Eats is particularly worth reading:

Still, the revised farm bill will ensure that citizens continue to pay for their food at least three times: 1) at the checkout stand; 2) in environmental cleanup and medical costs related to the consequences of industrial agriculture; and 3) as taxpayers who fund subsidies to a small group of commodity farmers deemed too big to fail.

FERN’s explainer video is also worth another look.

Documents