Weekend reading: Practicing Food Studies!

The exclamation point is because this is my department’s long-awaited book ,for which I wrote the Foreword and part of one of the last chapters.

If you are in the New York area, come to its celebration on April 1 at 5:3 p.m. at New York University’s Institute for Public Knowledge, 20 Cooper Square (South of 3rd Ave and North of The Bowery between 4th and 8th Streets), 5th Floor. For information and registration for the event, click here.

There will also be an online presentation of the book on April 29 through the NYU Library’s Critical Topics series. For details, watch for the announcement.

To buy the book from NYU Press, click here.

My department at NYU, now known as the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies, invented the field of Food Studies in 1996. Now, more than 25 years later, practically every college in America, and plenty outside the U.S., offers courses or programs about the role of food in society, commerce, and the environment.

Food studies is highly interdisciplinary (my doctoral degree is in molecular biology, for example). As NYU Press puts it, scholars from an enormous range of fields

felt limited by the conventions of their traditional discipline. Many gravitated to food studies to be able to describe and critically examine their specific areas of interest beyond the borders of academic disciplines.

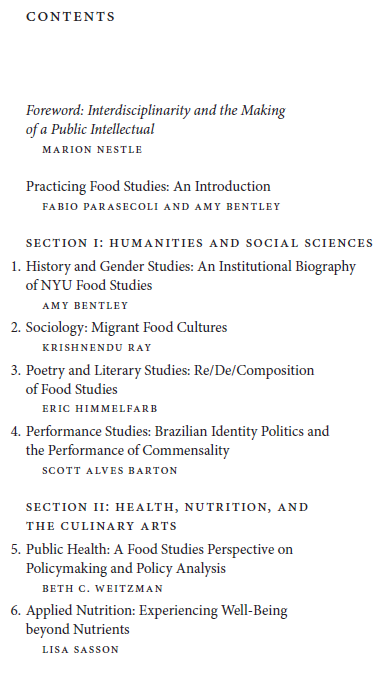

Faculty and doctoral graduates from our department wrote extraordinarily personal essays for this book to explain their connection to Food Studies and how this new filed made their work possible.

We do not necessarily agree with each other about what Food Studies is, exactly, and whether and how it fostered our work. We argue throughout, respectfully, of course.

I think the book is enormous fun and I could not be more proud of what it accomplishes.

Here are two of the blurbs:

“NYU’s Food Studies department has a lot to teach: about pedagogy, art, library sciences, the limits of traditional disciplinary fields, and the world beyond the academy. With essays that blend biography with analysis, this anthology finds the universal in the particular. Anyone interested in how to address the urgent and practical questions, while confronting the systemic ones, will find inspiration in this fine anthology.” ― Raj Patel, University of Texas at Austin

“Food studies provides a home for deeply interdisciplinary scholars; Practicing Food Studies packages that intellectual belonging into a single book that you’ll want to not just read but keep close. The editors, each a leading voice in the field, use NYU’s program as a case study that delivers a must-read history of food studies itself. Critical reflections, warmth, and candor leap from each page, fascinating and endearing at every turn.” ― Emily J.H. Contois, The University of Tulsa