Weekend reading: UK report on industry’s role in poor health

I’m just getting around to reading this report from three groups in the UK: Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), the Obesity Health Alliance (OHA) and the Alcohol Health Alliance (AHA): Holding us back: tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy food and drink.

I learned about it from an article in The Guardian:

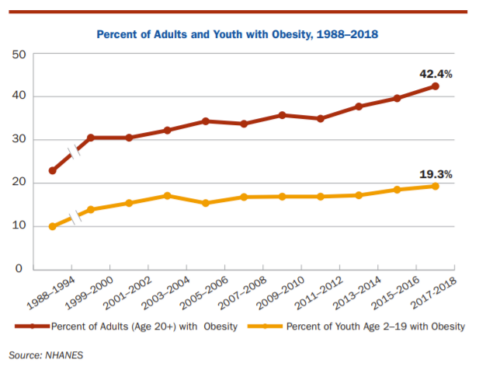

The report gives the health statistics: 13% of adults in England smoke, 21% drink above the recommended drinking guidelines, and 64% are overweight or living with obesity,.

NOTE: this report—unlike so many others—examines the political and economic causes of poor health. It says practically nothing about personal choice or responsibility. Instead, it focuses on industry profits and the costs of industry profiteering to society.

Big businesses are currently profiting from ill-health caused by smoking, drinking alcohol and eating unhealthy foods, while the public pay the price in poor health, higher taxes and an under-performing economy.

The wage penalty, unemployment and economic inactivity caused by tobacco, alcohol and obesity costs the UK economy an eye-watering £31bn and has led to an estimated 459,000 people out of work.

Meanwhile each year, the industries which sell these products make an estimated £53bn of combined industry revenue from sales at levels harmful to health.

The press release emphasizes the need to curb industry practices: More needs to be done to tackle the unhealthy products driving nearly half a million people out of work.

It recommends, among other things:

- The Government should take a coherent policy approach to tobacco, alcohol and high fat, salt and/or sugar foods, with a focus on primary prevention.

- Public health policymaking must be protected from the vested interest of health-harming industry stakeholders.

To do this, it suggests these actions to decrease sales of harmful products (my summary):

- Restrict advertising

- Set age limits for purchase.

- Do not allow prominent placement in shops.

- Raise prices; tax.

- Educate the public about risks (the one place where personal responsibility is considered).