Weekend (Forever) Reading: How to Write Recipes

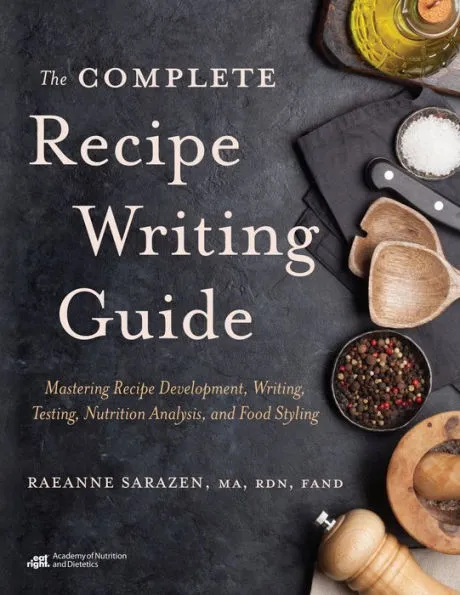

Raeanne Sarazen. The Complete Recipe Writing Guide: Mastering Recipe Development, Writing, Testing, Nutrition Analysis, and Food Styling. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2023.

You might think that writing a recipe is a simple matter of a handful of this and a pinch of that, but you would be oh so wrong.

This doorstop of a book—an absolute treasure—takes more than 400 pages to tell you how to do it right.

If only everyone who writes recipes would follow Sarazen’s advice, their recipes might actually work!

I can’t even begin to say how impressive this book is. Sarazen brings in an astonishing amount of information about food, nutrition, and diets into her discussions of how to think about recipes in general, but especially those for dishes aimed at improving health or dealing with health problems.

Sarazen is a critical thinker who deals with tough issues about recipes—cultural appropriation, intellectual property, nutritional unknowns—and works through them, one at a time.

If you have problems with gluten, fish, or FODMOPS (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), here’s what you need to know to deal with them.

This book is an encyclopedia of information about food, nutrition, and health, full of useful charts, explanations, and references. It’s a how-to manual for anyone who wants food to be delicious as well as healthy.

It’s really impressive and, as I said, a treasure.

Want it? Information about it and how to get it is here.