Weekend reading: FoodNavigator’s special edition on sweeteners

The industry newsletter, FoodNavigator.com, which I follow for its thorough coverage of this industry, has collected a set of its articles on sweeteners in a “special edition.”

Reminder: We love sweet foods. Sugars have calories and encourage us to eat more of sweet foods. Food companies wish they had a reasonable alternative to sugars that tasted as good and didn’t cause health problems.

Good luck with that! In the meantime…

Special Edition: Sweeteners and sugar reduction

Food and beverage manufacturers have a far wider range of sweetening options than ever before, from coconut sugar and date syrup to allulose, monk fruit and new stevia blends. We explore the latest market developments, formulation challenges, and consumer research.

- Consumer fear of sugar is mounting – but is it deserved and what alternatives will consumers accept? Using tactics such as “sin taxes” and a new bold-faced call-out for added sugar on the revised Nutrition Facts panel, public health advocates and regulators have targeted sugar as a primary caloric contributor in the ongoing obesity epidemic in the US – and sales data shows that consumers are listening… Read

- FDA guidance could prompt surge of interest in low-cal, tooth-friendly, rare sugar allulose: FDA draft guidance allowing allulose to be excluded from the total and added sugars declarations on the Nutrition Facts panel could generate a surge of interest in the rare sugar, predict formulators… Read

- SmartSweets to double store count in 2019: ‘We’re making candy cool again,’ says founder: Low-sugar confectionery startup SmartSweets is primed for solid expansion into mass and grocery this year, a move its founder says should bring Gen Y and Z back to the candy aisle… Read

- Sweeteners in focus: Where next for allulose, stevia, isomaltulose? Are sugar alcohols losing their luster, will allulose take off, and is stevia still hot? FoodNavigator-USA caught up with Icon Foods, Cargill and Beneo to explore formulation trends as brands come under increasing pressure to reduce sugar and keep labels clean… Read

- Are zero calorie sweeteners fueling, rather than fighting, the obesity epidemic? Are zero calorie sweeteners fueling, rather than fighting, the obesity epidemic by meddling with our metabolism or negatively altering our gut bacteria, as some critics claims? Or do they remain invaluable – and exhaustively tested – tools in the formulator’s toolbox?.. Read

- KIND challenges snack makers to better disclose sugar & sweeteners in products with an ‘X-ray’ popup: In response to the public’s growing aversion to sugar, manufacturers across categories have reformulated and launched products made with alternative sweeteners, but increasingly consumers don’t want those either – but they also can’t as easily identify them, suggests a recent survey conducted by KIND… Read

- Amyris bids for 30% slice of stevia market by 2022 with new Reb M sweetener: ‘On a quality basis, it’s a superior product. It simply tastes better’: Synthetic biology specialist Amyris has embarked on a mission to capture 30% of the global stevia sweeteners market by 2022 with a Reb M sweetener produced from cane sugar by a modified yeast strain, that it claims gives it a clear competitive advantage over rivals on cost and quality… Read

- Russell Stover corrects ‘brand communication problem’, brings sales growth to sugar-free chocolate product: Russell Stover enjoyed years of market dominance when it first launched its seemingly ‘too-good-to-be-true’ sugar-free chocolate line in the ’80s. But lately, its sugar-free chocolate sales have wavered as it fell out of favor with consumers who perceived the products to be at odds with a growing better-for-you lifestyle… Read

- Lily’s Sweets CEO: ‘It feels like a mainstream trend [reducing sugar] is being boosted by a micro-trend [keto]’: Consumers often say that if they’re going to indulge, they’d rather eat a small portion of something made with ‘real’ or familiar ingredients (butter, cane sugar, whole milk) than a more ‘processed’ low calorie/sugar/fat alternative… Read

- Finding stevia ‘polarizing’, beverage brand Petal switches up its sweetener ahead of national retail launch this summer: Sparkling botanical beverage brand Petal has had a busy first year as the company doubled its product line with three new flavors, underwent a reformulation (swapping out stevia and erythritol for organic agave), and is now primed for national distribution in the coming months, shared CEO and founder, Candice Crane… Read

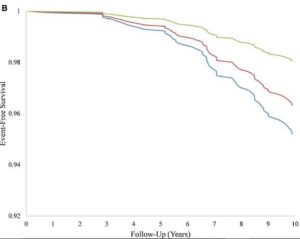

- Changes to Nutrition Facts label to call out ‘added sugar’ could save millions of lives, study suggests: Impending changes to the Nutrition Facts label that will require products to clearly label the grams and percent Daily Value of added sugar could prevent or postpone nearly 1 million cases of cardiometabolic disease and save billions in healthcare and societal costs over the next 20 years, according to a modeling study published this month in the journal Circulation… Read

- Yeast-based production process for tagatose could unlock low GI sweetener’s commercial potential, say researchers: A newly-engineered strain of yeast that can efficiently metabolize lactose into tagatose (a low-calorie, low-glycemic sweetener) may be the key to unlocking commercial-scale availability of the sweetener, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign believe… Read

- Sugar taxes: The global picture: Sugar taxes continue to hit the headlines, but the introduction of new legislation is never straight-forward. We take a look at 20 countries around the globe where sugar taxes have been in the news… Read

- SweetLeaf Stevia CEO: The sugar substitutes category is flat, but stevia products were up 31% YOY in Q1: If fat is back with a vengeance and protein remains on trend, sugar is now public enemy number one for many consumers, who want to cut down, but remain suspicious of the ‘natural’ credentials of some alternatives. FoodNavigator-USA caught up with Carol May (CM), CEO at Wisdom Natural Brands, maker of Sweetleaf Stevia, to find out what’s happening in the US sugar substitutes aisle… Read