Food labeling: yet another update

The FTC Forum last week got everyone going about food labels. Here are the latest items to hit my inbox:

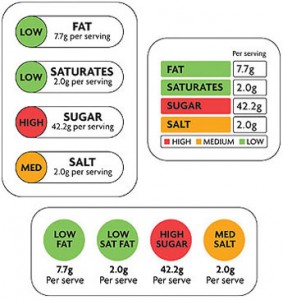

Traffic light front-of-package labels may do some good after all: As I explained in a previous post, British investigators did a study showing that the green-yellow-red traffic light dots on food packages do not necessarily help people make healthier choices. Now, another British scientist argues that the study showed no such thing; at best, it showed that more research is needed to see how consumers interpret and act on those signals.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) approves some (weak) omega-3 claims: Under great pressure from food companies desperate to make claims for omega-3 fatty acids, EFSA is allowing three, if somewhat grudgingly:

- DHA intake can contribute to normal brain development of the foetus, infant and young children

- DHA intake can contribute to normal development of the eye of the foetus, infant and young children

- DHA intake can contribute to the visual development of the infant

“Can,” I suppose, is a bit less conditional than “may,” but these are not strong claims. And they say nothing at all about making kids smarter. Under these rules, that “brain development” claim on Nestlé’s omega-3-fortified Juicy Juice drink (the one I find so absurd), would be OK. But anything more specific, the EFSA committee said, would have to be backed by further science.

FDA food labeling rules: if after all the fuss about serving sizes at the FTC Forum, you want to know what FDA really says about them, you can find the details on the FDA food labeling website. On that site, click on Label Formats/Graphics to find the current rules on serving sizes. Good luck making sense of them.

That’s more than enough about food labels for the moment. It’s the holidays and time to talk about something cheerier. Stay tuned.