On May 4, I was sent this press release from Tufts University : White House Announces Historic Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health.

Today, the Biden-Harris administration announced that it will hold a historic White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health this September…This will require bringing together diverse stakeholders, and raising the voices of people with lived experiences in food and nutrition insecurity, hunger, and diet-related disease…

To inform and help achieve these goals…[we]are announcing the formation of the Task Force on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health (Task Force), along with an accompanying Strategy Group on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health to advise the Task Force.

The Task Force brings together a diverse, non-partisan group of stakeholders to inform the goals of the White House Conference. This effort is not organized or endorsed by the White House, but represents an independent effort to convene voices from across the nation to help solve the issues at the heart of the Conference’s focus.

The official White House announcment makes clear that this conference is about both food insecurity and dietary determinants of chronic disease and COVID risk.

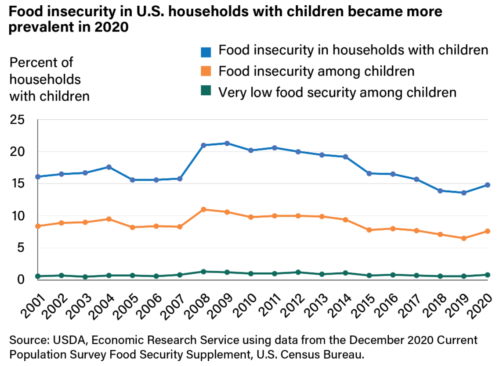

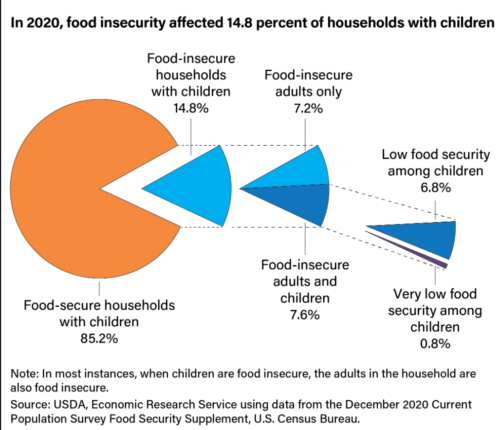

Millions of Americans struggle with hunger. Millions more struggle with diet-related diseases—like heart disease and diabetes—which are some of the leading causes of death and disability in the U.S.

The toll of hunger and these diseases is not distributed equally, disproportionately impacting underserved communities, including Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans, low-income families, and rural Americans.

This is exciting news. As I wrote in a previous post, if you are old enought or up on the history of US nutrition policy, you might remember the 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health. This led to the creation and strengthening of many nutrition programs, SNAP among them.

Tufts held a 50th anniversary conference at which I spoke (videos of the talks are here–I was on Panel 3 starting at about 17 minutes in).

And now for the questions.

Mine is this: What will be the balance between the conference focus on food insecurity (not controversial except for the cost) and the greatly needed fbut highly controversial focus on poor diets and their consequences for chronic disease and COVID risk?

Food safety lawyer Bill Marler asks: What about food safety?

Let this sink in: The CDC estimates 48 million people get sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die from foodborne diseases each year in the United States. It is not that I do not think a Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health is important and necessary, but could ya throw a bone to those sickened by foodborne illnesses?

E&E News notes: Biden nutrition conference may fire up climate debate on meat

Of all the food and agriculture interests bound to be represented in the Biden administration’s discussions, meat — and especially beef — may have the biggest messaging challenge, extolling its value in the diet against charges that Americans already eat too much and that raising and sending livestock to market contributes to climate change.

“We look forward to being a part of this important conversation and sharing the science-based, data-driven research regarding the immense environmental and nutritional benefits from cattle and beef production,” the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a producers’ trade group, told E&E News.

I suspect we will have many opportunities to weigh in on this.

I, for one, will be watching the progress on this conference with great interest. Stay tuned.

Resources

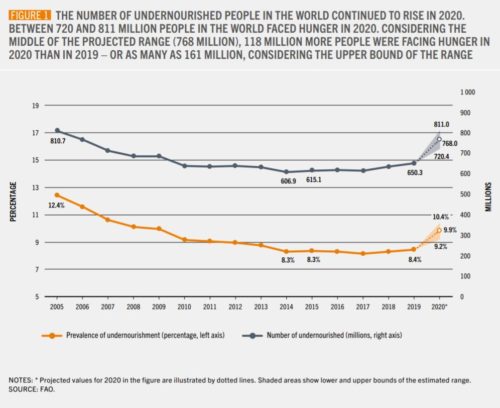

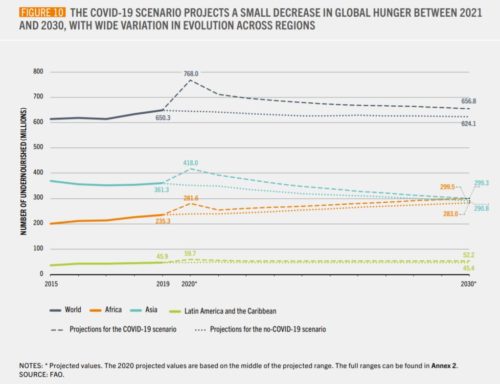

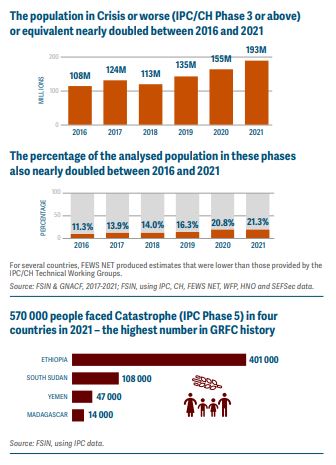

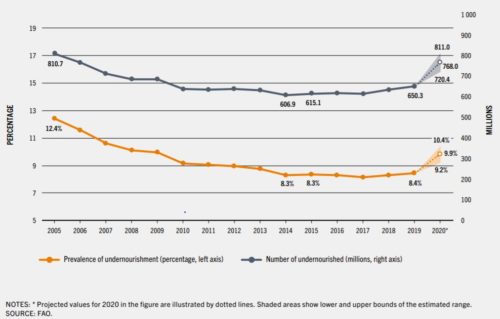

Regions in Asia and Africa have been hit hardest. The report gives the situation country by country.

Regions in Asia and Africa have been hit hardest. The report gives the situation country by country.