U.S. food insecurity: a failure of public policy

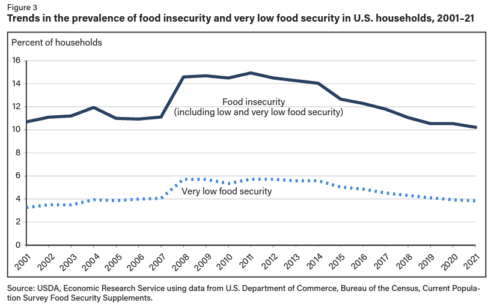

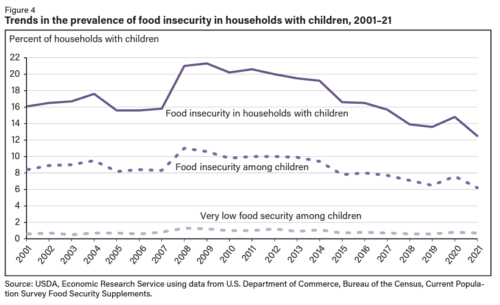

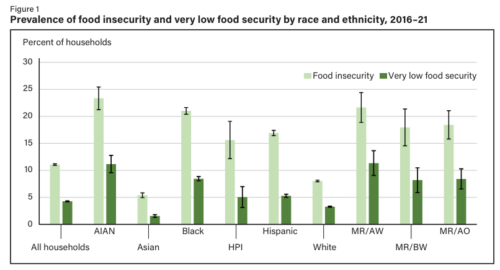

It takes a while for USDA to catch up to the data so its most recent report on food insecurity ends with 2021: “Household Food Insecurity Across Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2016-21.”

The highlights:

▪ The prevalence of food insecurity ranges from a low of 5.4% for Asian households to a high of 23.3% for American Indian and Alaska Native households. Food-insecure households had difficulty at some time during the year providing enough food for all household members because of a lack of resources.

▪ Food insecurity varied substantially by country of origin. Among Hispanic origin subgroups, food insecurity varied from 11.4% in Cuban households to 21% in Dominican households. Food insecurity among Asian origin subgroups ranged from 1.7% in Japanese households to 11.4% in other Asian households.

But where is the trend? The report did not include a trend line (could politics have something to do with this?).

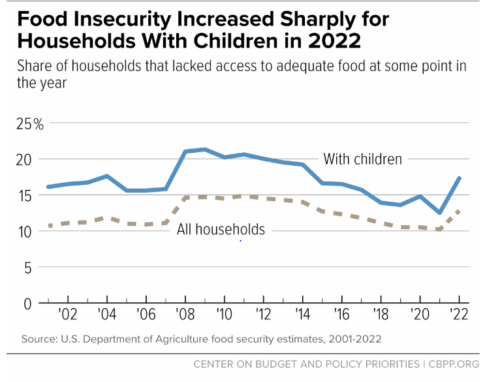

Fortunately, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities used the USDA data to produce this:

It’s a sad story of policy failure. We had one that worked during the pandemic. But Congress chose to end demonstrably effective measures. Politics wins over science, in this case tragically.

Overall, food insecurity increased from 10.2 percent in 2021 to 12.8 percent in 2022 — resulting in 10.3 million more people, including 4.1 million more children, who lived in households that experienced food insecurity in 2022 compared to 2021 — reflecting higher food costs and the phasing out of many pandemic relief measures.