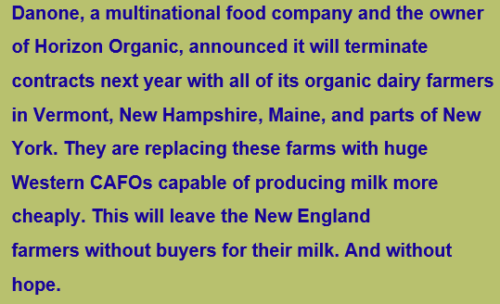

Bad move: Danone drops organic dairy contracts in Northeast

Lorraine Lewandrowski, a correspondent who keeps me up to date on the dairy industry, forwarded this bad-news article from the Vermont Digger: Danone, owner of Horizon Organic, to terminate contracts with Vermont farmers

The move represents the latest blow to an industry that has been struggling for years from rising production costs that have outpaced consumer prices. The number of dairy farms in Vermont has decreased by 37% in the past 10 years and by 69% in the past 24 years, according to a 2021 report from the Vermont Department of Financial Regulation.

Organic dairy farms decreased by 8% between 2010 and 2020. Vermont had a total of 181 organic dairy farms at the end of 2020, according to the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Vermont.

As the Real Organic Project explains it,

The Food and Agriculture Reporting Network’s FERN AgInsider had more information (behind a paywall)

The decision is just the latest squeeze on organic dairy producers, who face rising costs and pressures to consolidate…Danone North America, owner of Horizon Organic, said it had sent non-renewal notices to 89 producers in the Northeast. “We … did not make this decision lightly. Growing transportation and operational challenges in the dairy industry, particularly in the Northeast, led to this difficult decision…We will be supporting new partners that better align with our manufacturing footprint.”

This requires a blunt translation: organic milk in the Northeast costs more so Danone is cutting its losses.

Organic dairies in Midwestern and Western states, particularly Texas, have enormous herds and are able to produce milk at lower cost.

It’s cheaper for Danone to buy milk from them and ship it east than it is to buy from smaller local dairies. This is Big Organic Dairy in action, and it’s not pretty.

As an official of the Northeast Organic Dairy Producers Alliance says:

Danone, the parent company of Horizon Organics, believes it has adequate supply in the Midwest and Western parts of the U.S. and can get the milk at a lower cost from larger operations.

Comment #1: the hypocrisy

Danone proudly proclaims its B Corp status.

Danone cites its B Corp ambition:

an expression of our long-time commitment to sustainable business and to Danone’s dual project of economic success and social progress.

Social progress, anyone?

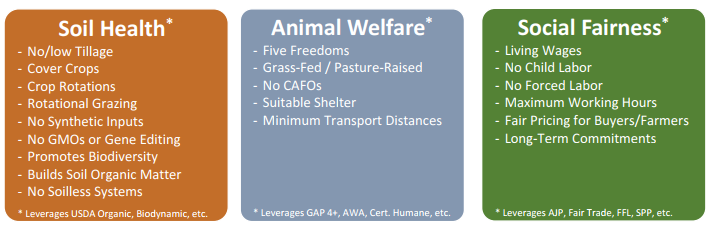

Comment #2: weakness in the organic herd definition

At the moment, the definition is ambiguous and makes it easy for Big Dairy to accumulate large numbers of animals that may meet the definition of organic in letter, but hardly in spirit.

The Organic Trade Association (OTC) explains this issue

The USDA National Organic Program regulations include requirements for the transition of dairy animals (cows, goats, sheep) into organic milk production. Milk sold or represented as organic must be from livestock that have been under continuous organic management for at least one year. This one-year transition period is allowed only when converting a conventional herd to organic. Once a distinct herd has been converted to organic production, all dairy animals must be under organic management from the last third of gestation.

But OTC says,

Due to a lack of specificity in the regulations, some USDA-accredited certifiers allow dairies to routinely bring non-organic animals into an organic operation, and transition them for one year, rather than raise their own replacement animals under organic management from the last third of gestation…This practice…is a violation of the organic standards and creates an economic disadvantage for organic farmers who raise their own organic replacement animals under organic management in accordance with the regulations.

The National Organic Coalition says:

the lack of consistent enforcement with regard to dairy pasture requirements as well as origin of livestock rules have contributed to the oversupply of organic milk in the market. This has had a devastating effect on organic dairy prices to farmers, and left many organic farmers and those transitioning to organic with stranded investments because there are no buyers for their milk.

The USDA first proposed to tighten the rules in 2015:

The proposed rule would require that organic milk and milk products must be from animals that have been under continuous organic management from the last third of gestation onward, with a limited exception for newly certified organic dairy producers.

Big Organic has taken advantage of these loopholes.

Danone is putting profit over social values. It does not deserve its B Corp status.

Presumably, USDA’s National Organic Standards Board is dealing with this issue. It needs to act quickly to protect small dairy farmers.

Nothing less than the integrity of the organic program is at stake.

If you want to help, write or call your elected representatives and ask them to get USDA to speed up rulemaking on this issue.