As it promised in response to a petition from the KIND fruit-and-nut bar company (as I discussed in a previous post), the FDA is now asking for public comment on what “healthy” means on food package labels.

You might think that any food minimally processed from the plant, tree, animal, bird, or fish would qualify.

But “healthy” is a marketing term for processed food products (not foods).

As Politico Morning Agriculture reminds us, things got complicated when KIND, which makes products from whole nuts, said its bars deserved to be called “healthy.”

In 2015, KIND received a warning letter from FDA arguing the company violated federal rules by using “healthy” on its packages. KIND then petitioned the agency, and, after an exchange about why the current definition is outdated, FDA decided to reverse course. For example, it requires that a food be low-fat to be labeled “healthy,” a standard that a nut-based bar doesn’t meet, while products like fat-free puddings do.

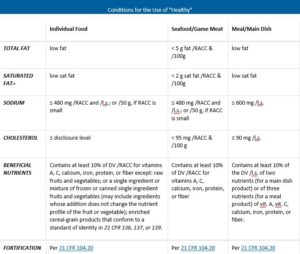

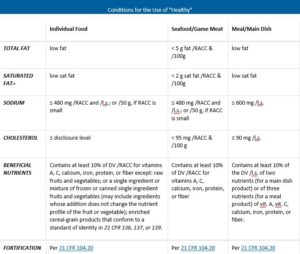

The FDA’s rules now say:

The term “healthy” and related terms (“health,” “healthful,” “healthfully,” “healthfulness,” “healthier,” “healthiest,” “healthily” and “healthiness”) may be used if the food meets the following requirements: 21 CFR 101.65(d)(2)

OK. I know you can’t read this (you can look for it here). The point is that to qualify as “healthy,” a product has to be low in fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol; relatively low in sodium; and contain at least 10% of the Daily Value per serving for vitamins A or C, calcium, iron, protein, or fiber (with some exceptions). There are also rules for levels of nutrients added in fortification.

The FDA wants input on whether all of this makes sense in the light of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines and the KIND petition.

In its inimitable FDA-speak:

While FDA is considering how to redefine the term “healthy” as a nutrient content claim, food manufacturers can continue to use the term “healthy” on foods that meet the current regulatory definition. FDA is also issuing a guidance document stating that FDA does not intend to enforce the regulatory requirements for products that use the term if certain criteria described in the guidance document are met.

If I correctly understand the meaning of “does not intend to enforce the regulatory requirements,” the FDA, while waiting for your comments, will allow manufacturers to call products “healthy” as long as the products:

(1) Predominantly contain mono and polyunsaturated fats regardless of total fat content; or

(2) Contain at least ten percent of the Daily Value (DV) per serving of potassium or vitamin D.

In other words, if your food product is made with a low saturated fat oil and contains potassium or vitamin D, it is by definition “healthy.”

Correction, September 29: An FDA official wrote to say that I didn’t quite get this right.

Actually, if a food exceeds the low fat requirement currently in our definition, we will not take any enforcement or compliance action as long as the food meets all of the other requirements in the definition, namely that it is low in saturated fat, cannot exceed the specified levels of cholesterol and sodium, and contains at least 10 percent of the daily value for beneficial nutrients.

Second, we are not saying that foods must contain potassium or vitamin D to be labeled as “healthy.” We are simply indicating that potassium and vitamin D can be substituted for the beneficial nutrients now listed in the current regulations, in line with the new Nutrition Facts label regulations.

My apologies to the FDA for misunderstanding the notice.

The FDA’s request is good news for KIND bars.

But it smacks of “nutritionism”—the use of these two single nutrients (as well as others on the short list of beneficial nutrients) as indicators of quality in processed food products (and don’t get me started on vitamin D, which is a hormone, not a vitamin, and best obtained by getting outside in the sun once in a while).

Understand: this effort is not about semantics; it is about marketing.

Would you like to weigh in on what you think qualifies a food as “healthy?” Here’s how: