My monthly (first Sunday) column in the San Francisco Chronicle is now out, this time on the horsemeat scandal.

Q: It makes me sick to think that anyone could eat horsemeat. I don’t see how it could get into so many foods. Tell me how I can be sure I’m not eating it.

A: From this side of the Atlantic, the discovery of horsemeat in European hamburger and frozen dinners is the most riveting of scandals, replete with DNA technology, veterinary drugs, impossible-to-trace supply chains, smuggling, organized crime and outright fraud – not to mention the usual finger-pointing, cover-ups and protestations of shock that accompany food crises.

It is easy to explain how horsemeat got into vast amounts of hamburger and prepared meals. Horses are expensive to house and feed. Something has to be done with them when they are no longer wanted for farming, transport, racing or recreation. Horsemeat is edible, even delicious to some, and costs less than beef.

Complications

In Europe, the supply chains are exceptionally complicated, involving countless companies in more than 21 countries that process, transport or sell horses or horsemeat. The complexity makes it relatively easy to use horses to smuggle people or drugs, to label horsemeat as beef or to slip it into hamburger.

This would just be a matter of economic fraud if people didn’t care whether they ate horsemeat. But some Europeans, and most Americans, care very much. Like you, many people are appalled at the idea of eating any companion animal, let alone one symbolic of the rugged West.

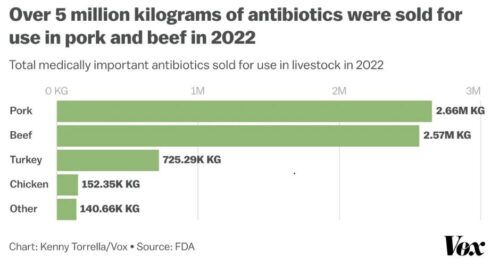

Beyond cultural prohibitions, there are other reasons to avoid eating meat from horses not raised for food. Horses are routinely treated with veterinary drugs, legal and not. The drug traces found in European horsemeat may be too low to cause harm, but hardly seem likely to promote human health.

How long horsemeat has been passed off as European beef is unknown, as is why officials in Ireland decided to do DNA tests on supermarket meals in the first place. Whether done as routine testing or because of a tip, the results were startling. More than one-third of the tested “beef” samples contained horsemeat. Later tests in Great Britain identified “beef” meals made entirely from horsemeat.

This, as the Guardian’s writer Felicity Lawrence wrote in her guide to the scandal, can only be “industrial scale adulteration.”

The ensuing crisis forced many food companies and retailers to recall vast numbers of products, some intended for school meals. Nestlé (no relation) recalled pasta meals, but issued assurances that such products do not leave Europe and that none of its American products contains horsemeat-laden European beef.

What to make of this? In our food studies programs at New York University, we discuss food as a marker of cultural identity. People in other nations eat horsemeat. But like you, about 80 percent of Americans are appalled at the idea of eating horsemeat and oppose slaughtering horses for food or any other reason.

Yet horsemeat used to be eaten by Americans (and still is, by some), and even more so by pets. As Malden C. Nesheim and I wrote in our book about the pet food industry, “Feed Your Pet Right,” horse slaughterhouses created pet food companies to dispose of the meat. Through the 1940s, nearly all domestic horsemeat ended up in pet food.

Under pressure from horse lovers and animal welfare advocates, pet food companies replaced horsemeat with meat from other animals. Although horsemeat is permitted in pet food, and in theory could show up in rendered byproducts and meals, no American company would knowingly use it as an explicit item in an ingredient list. One can only imagine the uproar if it did.

Inspection issues

In 2007, Congress blocked the Department of Agriculture from inspecting slaughterhouses, effectively banning their use. As unintended consequences, the 140,000 or so unwanted horses each year had to be transported to slaughterhouses in Canada or Mexico, and populations of neglected and abandoned horses increased. As a result, Congress permitted horse slaughterhouses to reopen last year, but the USDA has yet to authorize inspectors to work in them.

Could American beef be contaminated with horsemeat? We had a similar scandal in the 1950s. But if U.S. officials are testing hamburger for horsemeat DNA these days, they aren’t saying.

Because horsemeat is not produced here, it won’t be in butcher shops or supermarkets – unless the stores imported it or acquired contaminated products before the recalls, or unless the USDA assigns inspectors and allows horse slaughterhouses to reopen. Right now, without DNA testing, you can’t be sure.

You find this alarming? Short of going vegetarian, you have an option: Buy kosher meat. Jewish dietary laws prohibit horsemeat – horses are not ruminants and do not have cloven hooves – and kosher slaughterhouses are diligent about excluding forbidden animals.

This gives the horsemeat scandal one clear winner: Sales of kosher meat are booming.