Harold McGee.

Harold McGee, author of the astonishing On Food and Cooking, sent me a copy of his equally astonishing new book, this one an encyclopedia of the smells of everything—the “osmocosm.”

I am happy to have it. He’s produced a life-changing book. I will never think of smells in the same way again.

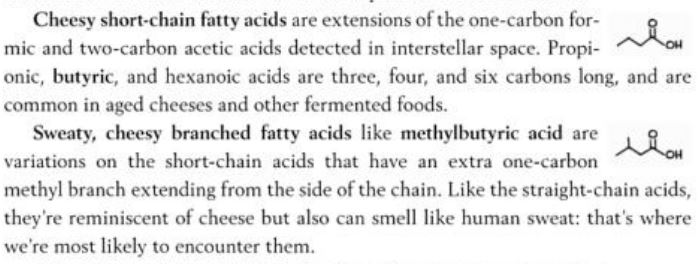

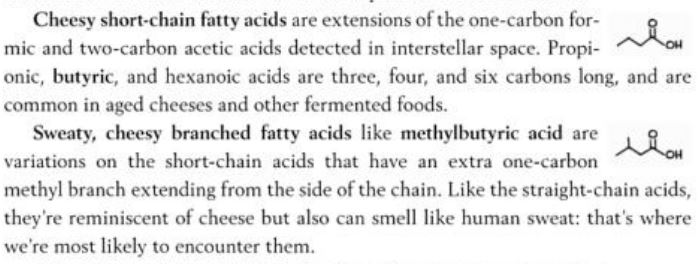

For starters, the book is brilliantly designed with elegant charts, key terms in bold, and chemical structures (yes!) right next to the terms in miniature on a light grey background, set off from the text but right there where they are needed. Here’s an example from the pages that Amazon.com makes available. This excerpt comes from a section on the smells of chemical compounds found in interstellar space (p. 19—and see my comment on the page number at the end of this post).

Interstellar space? Well, yes. Also animals, pets, and human armpits, along with flowers, spices, weeds, fungi, stones (they have bacteria and fungi on them), asphalt, perfumes, and everything else that smells or stinks—as well as foods, of course.

McGee must have had fun writing this.

It’s exactly becasue CAFOs [Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations] are offensive and harmful that the volatiles of animal excrement have been so well studied. Crazily but appropriately, chemists borrow the terminology of top, middle, and base notes from the perfume worls (see page 477) to describe the smells of CAFOs. The top notes, very volatile and quickly dispersed, are ammonia and hydrogen sulfide. The more persistent middle notes include amines, thiols and sulfides, aldehydes and alcohols and ketones. The constantly present base notes are the short-chain straight and branched acids, cfresol and other pehnolics, and skatole. In a 2006 study of swine and beef cattle operations, barnyard cresol was identified as the primary offensive odor, and could be detected as far as ten miles (sixteen kilometers) downwind. It’s probably the first long-distance hint I get of that I-5 Eau de Coalinga (p. 71).

But let me be clear: this is an encyclopedia, demanding close attention to the chemistry. Sentences like this one come frequently: “The branched four-carbon chain (3-sulfanyl-2-methyl butanol) has its branch just one carbon atom over from the otherwise identical molecule in cat pee” (p.121).

But this blog is about food. McGee’s discussion of food smells are riveting. For example:

- The standard basil varieties in the West today mainly produce varying proportions of a coupld of terpenoids, flowery linalook and fresh eucalyptol, and the clove- and anise-smelling benzenoids eugenol and estragole. But when it comes to a dish in which basil stars—peto alla genovese, the Ligurian pasta sauce of pounded basil, garlic, nuts, and cheese—Italians are more particular (p. 255).

- In 2014, I made a pilgrimage to a celebrated durian stall in the outskirts of Singapore and found that most of the half-dozen varieties I tried tasted of strawberries and a mix of fried onions and garlic. I enjoyed them enough to smuggl one into my hotel room…After just an hour or two its royal presence filled the room and became unbearable. I had no choice but regicide, and disposed of the body like coCanned sntraband drugs, flushing it in pieces down the toilet (p. 333).

- The dominant note [in beef stews], described as “gravy-like,” came not from the meats, but from the onions and leeks! The volatile responsible turned out to be a five-carbon, one-sulfur chain with a methyl decoration, a mercaptomethyl pentanol, MMP for short. It is formed by a sequene of reactions, the first causaed by heat-sensitive onion enzymes, then ordinary chemical reactions that are accelerated by heat. So its production is encouraged by chopping or pureeing these alliums (but not garlic) well before cooking them to let the enzymes do their work, the cooking slowly for several hours (p. 513).

- Canned sweet corn is dominated by seaside-vegetal dimethyl sulfide, acetyl pyrroline, and a corny thiazole (p. 519).

- Swiss Appenzeller is notably strong in sweaty-foot branched acids (p. 567).

It should be clear from these excerpts that this is a reference work—a field guide—just as advertised. If you read it, you will learn more than you ever dreamed possible about the volatile molecules that we can and do smell.

Nose Dive will go right next to On Food and Cooking on my reference shelf.

But uh oh. How I wish it had a better index.

For a book like this, the index needs to be meticulously complete—list every bold face term every time it appears—so readers can find what we are looking for. This one is surprisingly unhelpful.

I found this out because I forgot to write down the page number for the fatty acid excerpt shown above. I searched the index for most of the key words that appear in the clip: fatty acids, short and branched; butyric; methylbutyric; hexanoic; cheesy; intersteller space. No luck. I had to check through all of the fatty acid listings and finally found it under “fatty acids, and molecules in asteroids, 19.” Oh. Asteroids. Silly me.

I also forgot to note the page for the CAFO quote. CAFO is not indexed at all, even though it appears in bold on the previous page, and neither does its definition, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation.

McGee refers frequently to “Hero Carbon,” the atom basic to odiferous molecules. I couldn’t remember where he first used “Hero” and tried to look it up. Not a chance.

This book deserves better, alas.

Penguin Press: this needs a fix, big time.