Sugar policy: absurd but apparently permanent

The House version of the farm bill is in a mess right now and there is much to say about both its process (highly politicized) and content (thoughtless, mean-spirited, and just plain nasty). I will be singling out specific pieces for comment every now and then.

Let’s start with a proposed amendment that the House soundly defeated. AP reporter Candace Choi succinctly summarized the significance of this defeat: Big Sugar beats back Big Candy.

I’ve discussed our absurd Big Sugar policy in previous posts.

For decades, despite endless reform attempts, U.S. sugar policy has protected the interests of producers of sugar cane and sugar beets.

Basically, current policy maintains the price of domestic sugar at a level higher than the market price in order to protect politically powerful sugar cane growers in Louisiana and Florida, and somewhat less powerful—but far more numerous—growers of sugar beets.

American consumers pay more for sugar, but only an average of $10 per capita per year, not enough to get people upset.

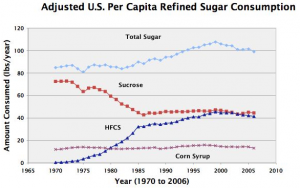

The big losers are candy makers and other commercial users of cane and beet sugars. Soft drink makers are relatively unaffected because they mostly use high fructose corn sweeteners.

Reps. Virginia Foxx (R-N.C.) and Danny K. Davis (D-Ill.) sponsored an amendment to the farm bill that would require the sugar industry to repay the government if and when its loan program operates at a loss.

The sugar program is not supposed to cost taxpayers any money because it keeps prices high enough so that loans get paid back. But in 2013, prices fell and the USDA had to buy surplus sugar at a loss of $259 million. The Congressional Budget Office says that the sugar program will cost about taxpayers about $76 million over the next decade.

Nevertheless the House defeated the sugar amendment by a vote of 137 to 278. How come? Louisiana and Florida are key election states. Sugar beet growers operate in practically every northern state in the U.S.

The successful fight to defeat the amendment was led by the American Sugar Alliance. The Washington Post reports how the Alliance paid for an advertising campaign positioning the growers it represents as victims.

A full-page ad in last Wednesday’s Wall Street Journal featured a picture of two Louisiana sugar planters and the words: “Excluding us from loans available to other crops isn’t ‘modest reform,’ it’s discriminatory. Don’t cut sugar farmers out of the Farm Bill. Oppose harmful amendments.”

And so the House did.

This is only the latest episode in attempts to reform sugar policy. Chalk this one up as a win for Big Sugar, as Candace Choi so nicely pointed out.