Milk marketing, Australian style

I’m in residence at the Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney for a bit and am getting the chance to learn the Australian version of food politics.

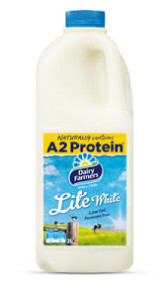

I like milk with my coffee. Here’s all they had at a local corner store.

The banner on the label says that it “NATURALLY contains A2 protein.*”

A2 protein? What’s that?

The label, alas, is not much help.

*Dairy Farmers milk naturally contains A2 protein as well as A1 protein. Of those proteins, our tests to date confirm that 50-7-% is A2.

So? Should we care? YES, according to the A2 Milk Company:

The two main types of milk proteins are the casein and the whey proteins. These make up to 80% and 20% of the protein content of cows’ milk respectively. Other proteins present at low levels in milk include antibodies and iron carrying proteins.

Beta-casein makes up about one third of the total protein content in milk. All cows make beta-casein but it is the type of beta-casein that matters. There are two types of beta-casein: A1 and A2. They differ by only one amino acid. Such small differences in the amino acid composition of proteins can result in the different protein forms having different properties.

According to a press account,

For nearly 20 years, there have been claims that the A2 beta-casein protein is easier to digest than A1, but it’s been dismissed as unscientific. This pilot study at Curtin University…found subjects on an A2 milk diet reported less bloating abdominal pain, and firmer stools, by staying off A1 beta-casein.

But this milk contains both A1 and A2 proteins.

In any case, guess who funded this research!

Comparative effects of A1 versus A2 beta-casein on gastrointestinal measures: a blinded randomised cross-over pilot study. Ho S, Woodford K, Kukuljan S, Pal S. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014 Sep;68(9):994-1000. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.127. Epub 2014 Jul 2.

- Conclusions: These preliminary results suggest differences in gastrointestinal responses in some adult humans consuming milk containing beta-casein of either the A1 or the A2 beta-casein type, but require confirmation in a larger study of participants with perceived intolerance to ordinary A1 beta-casein-containing milk.

- Funding: This study was supported by a grant from A2 Dairy Products Australia, who also supplied the milk. A2 Dairy Products Australia had no role in the data analysis of this study.

The label has more to say:

Of course, it’s made here in New South Wales and it’s Permeate Free—so it’s less processed and simply delicious.

Permeate Free? What’s that? A local website explains:

Permeate is simply a collective term for the natural lactose, vitamin and mineral components which are separated from fresh milk by a process called ultrafiltration. Because milk is a natural food (and tastes different from cow to cow) filtering the permeate out (before putting it back in) allows processors to regulate their milk so they can control the taste, protein and fat content.

Apparently, Australian labeling authorities allow this process to qualify as “natural?”

The label lists these ingredients: Skim milk, milk, milk solids [the source of the extra A2 proteins and the Permeate?].

Next time, I’ll look for a product with precisely one ingredient: milk.