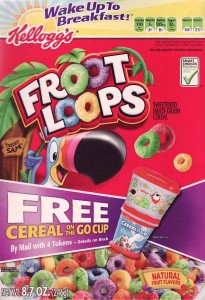

We now have a piece mentioning the Smart Choices program in The Economist as well as a letter from Dr. Eileen Kennedy, the member of the Smart Choices program committee to whom the quotation about Froot Loops, “Better than a doughnut,” is attributed.

The Economist discusses the booming business of functional foods: “Consumers are swallowing such products, and the marketing claims that come with them.” It mentions the fuss over Smart Choices, but the best part is the caption to the illustration that comes with it.

It's practically spinach

And, I’ve been sent a copy of an e-mail letter to alumni from Dr. Eileen Kennedy, dean of the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, explaining her participation in the Smart Choices program:

Dear Friedman School Alumni,

There is an issue that has emerged as a result of a NY Times article that appeared in the business section on Sept 5, 2009. Since I believe I was grossly misquoted in the article and that the article does not accurately depict the Smart Choices program, I want to share with you some background on this program and my involvement.

In 2007, I was invited to join the Keystone Roundtable on Food and Nutrition. Keystone is a non-profit organization that brings individuals together around potentially controversial issues. The roundtable included health organizations, food companies, retailers, and academic researchers from a variety of U.S. universities. I was one of the academics who served pro bono on the roundtable. Initially, we met to discuss revisions to the FDA nutrition label. Ultimately, we decided to address the issue of Front of Pack Labels on food products. The final recommendations of the group were based on consensus science including the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the FDA definition of healthy, WHO recommendations and the Institute of Medicine Scientific reports. The program that emerged from this meticulous process is called “The Smart Choices Program (SCP).” Food products that qualify as “better for you” get a check mark as well as disclosure of calories per serving and number of servings in a product.

I believe there are three major advantages to this program in addition to the rigorous scientific underpinnings.

First, the SCP is intended to improve food patterns at point of purchase – the super markets. To do this, food products are divided into 19 categories – based on research – that reflect how people buy food. All fruits and vegetables without additives automatically qualify.

Second – and a major plus – the program was tested prior to launch with consumers.

Finally, food companies who participate in the program have agreed to abandon their proprietary systems and adopt one system – the Smart Choices Program.

Thus, thousands of products using the SCP check mark will reach millions of consumers. It is a credit to the social responsibility of participating companies that because of the strict nutrition criteria, fewer of the individual food products will qualify for the Smart Choices Program.

As a non-industry board member, I have been targeted by negative emails, letters and even some phone calls. I regret that some of this hostility has been focused on the Friedman School and Tufts University and must note that I serve as an individual on the Smart Choices Program. Tufts University is not involved with it….

As nutritionists, we know that, in many ways, the science of nutrition is straight-forward. It is the translation of science into action that is often complex and can be contentious. Within our field, there are many opinions on how to improve the nutritional well-being of people worldwide. It is precisely at an academic institution like Tufts that we should have a respectful and open dialogue about these issues….For additional information, you may also want to go to www.smartchoicesprogram.com….

The letter gives me a chance to repeat a few points that I have made in previous posts (see Smart Choices, Scoring Systems) and on the general matter of corporate sponsorship of nutrition activities (tagged as Sponsorship).

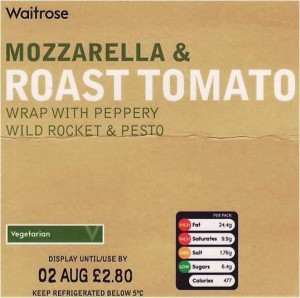

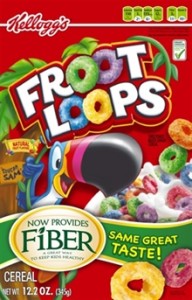

First, this enterprise was paid for by participating companies to the tune of $50,000 each for a total of $1.67 million. Social responsibility? I don’t think so. Companies usually get what they pay for. Hence: Froot Loops.

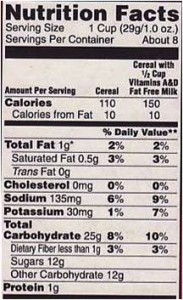

Second, a comment on the research basis. I have written extensively in Food Politics and in What to Eat about the influence of food companies on federal dietary guidelines and the compromises that result. Even at its best, the process has to be impressionistic and cannot be either meticulous or rigorous. The guidelines are meant to be generic advice for healthful eating. They were never meant to be used – and cannot be used – as criteria for ranking processed foods as healthful.

The FDA standards for comparison to Daily Values on food labels are also worth a comment. They were the basis of Hannaford supermarkets’ Guiding Stars program, which awards one, two, or three stars to foods that meet FDA-based criteria. By those criteria, Froot Loops does not qualify for even one star. If Smart Choices had relied on FDA criteria, such products would not be check marked.

Dr. Kennedy makes some excellent points in her letter and I particularly agree with one of them: nutritionists differ in opinion about how best to advise the public about diet and health. Mine is that the Smart Choices program is a travesty and the sooner it disappears, the better.

September 29 update: The L.A. Times weighs in with a story (which quotes me). It’s got another great comparison from a member of the Smart Choices committee: “Cereal provides an array of nutrients and is a good breakfast…especially if the alternative is a sweet roll.” My son, who saw the story, has this comment: “Hey! I think Froot Loops are a “Smart Choice.” After all, they have “froot,” don’t they? And maybe no nutritionist you know would recommend Froot Loops for breakfast, but what about for lunch or dinner?”

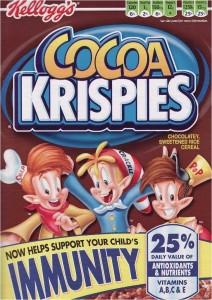

I don’t know how you interpret this but my mind boggles at the very idea that eating Cocoa Krispies might protect kids against swine flu.

I don’t know how you interpret this but my mind boggles at the very idea that eating Cocoa Krispies might protect kids against swine flu.

OK. I understand that companies want to market their processed foods, but I cannot understand why nutrition societies thought it would be a good idea to get involved with this marketing scheme. It isn’t. The American Society of Nutrition gets paid to manage this program. It should not be doing this.

OK. I understand that companies want to market their processed foods, but I cannot understand why nutrition societies thought it would be a good idea to get involved with this marketing scheme. It isn’t. The American Society of Nutrition gets paid to manage this program. It should not be doing this.