FDA unapproves tara flour as a food ingredient

Last week, the FDA essentially took tara flour out of the food supply.

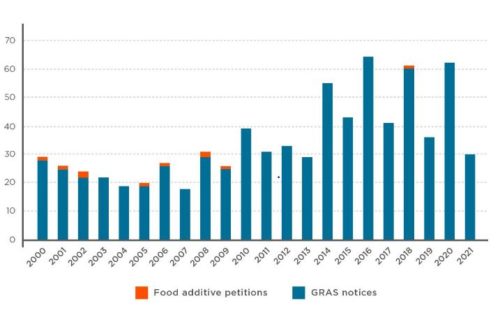

Today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) posted on its website its determination that tara flour in human food does not meet the Generally Recognized As Safe (or GRAS) standard and is an unapproved food additive. The FDA’s assessment of the ingredient is detailed in a memo added to the agency’s public inventory.

The FDA explained what this is about.

In 2022, Daily Harvest used tara flour in a leek and lentil crumble product which was associated with roughly 400 adverse event reports. The firm took prompt action to voluntarily recall the product and conduct their own root cause analysis, during which they identified tara flour as a possible contributor to the illnesses. To date, the FDA has found no evidence that tara flour caused the outbreak; however, it did prompt the agency to evaluate the regulatory status of this food ingredient.

Daily Harvest makes frozen vegan meals for home delivery. One of these meals contained tara flour. Of 26,000 such meals sent out, 400 caused eaters to become desperately sick, some needing hospitalization, some needing surgery (I’ve met some of them).

In my posts, I speculated about why tara flour could cause such severe reactions.

Bill Marler, the food safety lawyer representing a great many of the victims, pushed the FDA to get tara flour out of the food supply before anyone else got sick. His December 2023 letter reviews what is known about this situation to date. The FDA paid attention!

Now, two years later, the FDA is doing what it can to prevent tara flour from getting into the food supply. Good.

Here’s what I’ve had to say about this:

- The Daily Harvest mystery—a cause at last?

- The Daily Harvest recall mystery: update

- Tara flour: a quick review of the research

- What’s up with the Daily Harvest recall?

Here’s what Food Safety News has to say. It notes more cases than are reported by the FDA, many of them represented by food-safety attorney Bill Marler.

Daily Harvest seems to have survived this tragedy, is still in business, and right on top of currents trends. Its latest:

Daily Harvest’s January Jumpstart program features GLP-1-focused meal plans: Daily Harvest’s debut of its GLP-1 Companion Food Collection as part of its quick-to-prep January Jumpstart plan includes “meals made with only real foods that are calorie-conscious while delivering ample vitamins and minerals,” Carolina Schneider, MS, RD, Daily Harvest’s nutrition advisor, told FoodNavigator-USA…. Read more