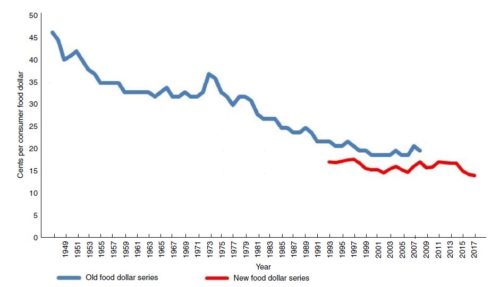

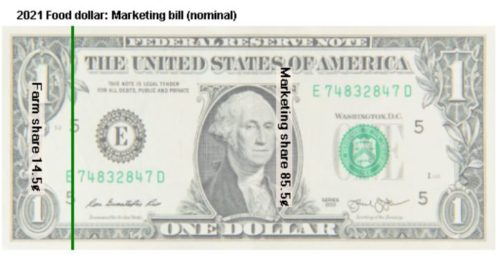

USDA’s food dollar: farm share is 14.5 cents

The USDA has just published its latest food dollar series. (And see below for international data.)

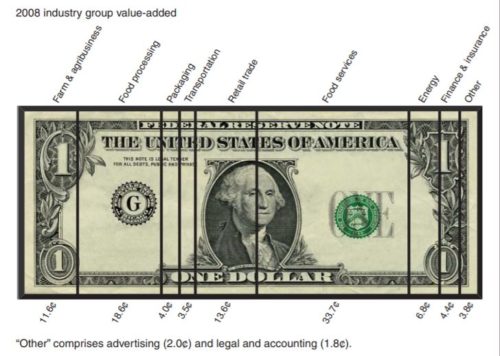

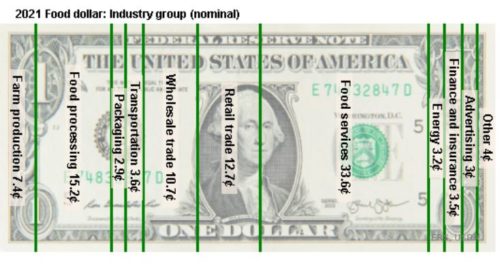

And here’s how all that is distributed.

If you are a farmer, you get an average of just over 7 cents on the dollar.

The real money is in processing, retail, and food service—added value, indeed.

The Food and Agriculture Organization is now providing this information for other countries at its new Food Value Chain domain. This is an interactive site that is not particularly intuitive to use; it will take some fiddling to lmake it work.

The new FAOSTAT domain, which will steadily expand coverage, has information for 65 countries from 2005 through 2015. It shows that around 20 percent of expenditure on food at home accrues to the farmer, around one-fourth to processing, and nearly half to retail and wholesale trade.

Meanwhile, only around 6.7 percent of consumer expenditure on food away from home accrues to the farmer. That figure is steadily decreasing even, highlighting the need to pay attention to the post farm-gate dimension of the food value chains.

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.