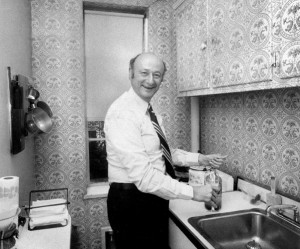

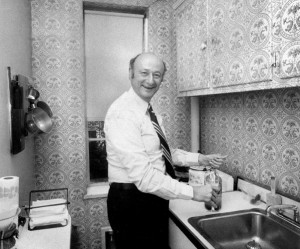

Among the many articles about former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, who died on February 1, almost all mentioned his rent-controlled apartment in Greenwich Village. Few noted that NYU owned its building.

Several readers of this blog, knowing that I have lived in that apartment since Koch moved out, suggested I say a word about it. This is not the first time I’ve been asked. I told some of the story to the New York Times in 2002.

As the Times reported last week,

In 1967, he [Koch] moved to a one-bedroom unit at 14 Washington Place. This was the rent-controlled apartment that he originally considered more appealing than Gracie Mansion. It had a working fireplace and the occasional rodent visitor — though no cockroaches. And besides, he told a reporter, “I know where everything is.”

“It’s small. I like it. It’s me,” he said, just before assuming office. “I don’t care what anybody says: I won’t give it up.”

I arrived in New York in the fall of 1988 when I joined the NYU faculty as chair of what was then called the Department of Home Economics and Nutrition (now the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health).

NYU rents housing to some of its faculty, and assigned me to a small, one-bedroom apartment in what used to be the maid’s quarters at the back of one of the university’s town houses on Washington Square. The apartment had no kitchen. The refrigerator in the living room. When I complained, they insisted this was an improvement; the previous tenant kept it in her bedroom.

I was new to New York real estate, and longed for something more appropriate for someone who cares about food.

I got my chance a year later when Ann Marcus became dean of my school. She arranged for me to meet the head of NYU’s housing office to discuss options. I missed California and wanted a garden. Well, he said, it’s too bad about the Koch apartment. It has a large terrace—but Koch will never move.

That surprised me. I had just read that Koch, who had just lost the primary election to David Dinkins, was negotiating for an apartment at 2 Fifth Avenue. His sister Pat worked at NYU. I went straight to her and explained that this was about an apartment in New York. Was her brother really leaving? “He’s packing this weekend,” she told me, “go take a look.”

I did and found the Mayor on the telephone surrounded by bodyguards.

They said “Do you have any idea how lucky you are? His new apartment may be bigger, but this one is nicer.”

Really? This seemed like a stretch. Every inch was covered with furniture and the closets were so full that stuff fell out of them when I opened the doors. Yards of dark green paint were hanging off the ceilings. The window shades were drawn—security—and the place was dark.

But the terrace!

By the time I moved in three months later, NYU had done a renovation. The walls shone with white paint. The galley kitchen had been converted to a pass-through. The fireplace worked. The terrace had new tiles. I could see the Empire State Building from the living room window. It would do just fine.

I still had to cope with the bullet-proof windows that hardly opened, the heavy security doors, and the secure telephone lines that cost $300 to replace. And the rent was a lot more than Koch’s $475.

That was 1990. I’ve now lived in the apartment as long as Koch did. I’m still grateful to him for leaving at just the right time.

I feel the same way about the apartment that he did:

It’s small. I like it. It’s me. I won’t give it up.