Melamine in Chinese infant formula: the saga continues

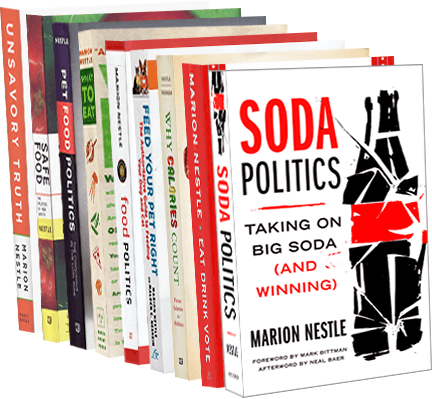

My interview with Eating Liberally this week concerns the wake of the pet food recalls that I wrote about in Pet Food Politics: The Chihuahua in the Coal Mine. Some Chihuahua! Now we have the Chinese infant formula scandal and don’t we wish we had Country-of-Origin Labeling? It’s been a busy few days on the scandal. The toll so far is 2 babies dead and 1253 sick, with 340 still in the hospital, and 53 of these are in serious condition. The Chinese have arrested two brothers who run a milk collection center on suspicion that they added melamine to make the protein content appear higher. An investigation of dairy producers found 22 to be producing milk contaminated with melamine. The largest of these dairies is owned in part by Fonterra, a New Zealand company. Fonterra says it tried to get the formula recalled earlier but the Chinese refused.

September 17: Today, it’s 3 babies dead, 1,300 in the hospital, and 6,244 sick. They were adding melamine to cover for diluting the milk with water. Hmm. Just like we used to do in the early years of the 20th century before passing pure food laws. Regulation, anyone?

When I was in New Zealand last year at a ministerial agriculture meeting, I heard a lot about how ranchers were giving up on sheep and starting large dairy farms to supply milk to China. This meant the end of pristine streams and sheep dotting the landscape.