On Netflix now: Poisoned

Poisoned, the food safety film featuring the lawyer, Bill Marler, is now available to watch on Netflix.

I wrote about earlier when I saw it at the Tribeca Film Festival.

It’s totally worth watching, and not only because I have a cameo in it.

Bill Marler explains why. I reproduce his post with permission.

After Netflix Poisoned – What would I do with a Food Safety Magic Wand?

Over two months ago, while watching the premiere of the documentary, “Poisoned,” at the Tribeca Film Festival in NYC, I got thinking again about how little in the past 30 years I feel I have moved the needle on food safety – pathogens and certainly, human nutrition. Now that “Poisoned” is up on the Netflix platform, it has become the most watched documentary in the world – at least for the last few days.

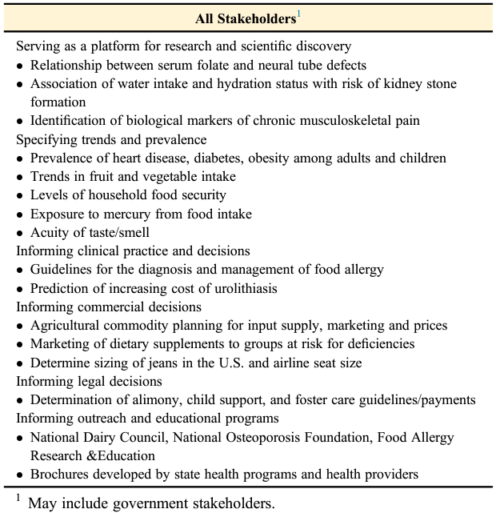

The real issues to me is how do we engage the food industry, policy makers, academics and most importantly consumers, to focus on driving the numbers down on the pathogens that kill us quickly and the products that kill us over time?

I will focus on pathogens as I have for the last 30 plus years. I will leave it to some very smart people who are rightly concerned about the millions of us who become sick and die due to inadequate nutrition – especially the millions of illnesses and deaths due to heart disease, diabetes and obesity caused by ultra-processed foods, salt, sugar, and fat.

There is so much to do, and the list is long. So, what would I do with a Food Safety Magic Wand on day one?

- Vaccinate. The first thing I would do is mandate that all food service workers be vaccinated against hepatitis A. Perhaps to some, not the most pressing food safety issue, but it is forefront of my mind. In the past few months, I finished up litigation around a hepatitis A outbreak involving one ill food service work who infected nearly 50 people, hospitalizing most, killing four and causing two liver transplants. With regret, I forced a family-owned restaurant chain to file for bankruptcy. All of this could have been prevented by a safe vaccine that has been around for decades. It is time for the restaurant industry and the CDC to step up.

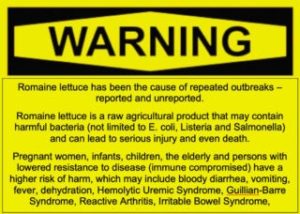

- Investigate. Invest in public health surveillance over human pathogens, like, Listeria, E. coli and Salmonella, etc. A dirty truth is that most culture-confirmed illnesses are never attributable to a food source, so people never know what sickened or killed them. Not because the source was not food, but because we fail to invest adequate resources in the epidemiologists that investigate illnesses and track those illnesses to the cause. Tracking illnesses to the cause gets tainted product off the market and helps us all understand what products and producers to avoid. We need to continue to invest in the science of whole genome sequencing, so we know with certainty which pathogens are causing which illnesses. Foodborne illness epidemiology helps us understand the root cause of an outbreak and helps prevent the next one from happening at all.

- Relegate. Allow public health officials access, especially during an outbreak investigation, to all areas around farms that grow fruits and vegetables. It is long past time to allow investigators access to neighboring cattle, dairy, chicken, or hog operations that spill billions of deadly pathogens into the environment, via air or water. We need to think of our growing regions as an integrated system and that all sectors responsible need to play a role. Access allows investigators to understand the likely cause of an outbreak, and again, what can be done to prevent the next one.

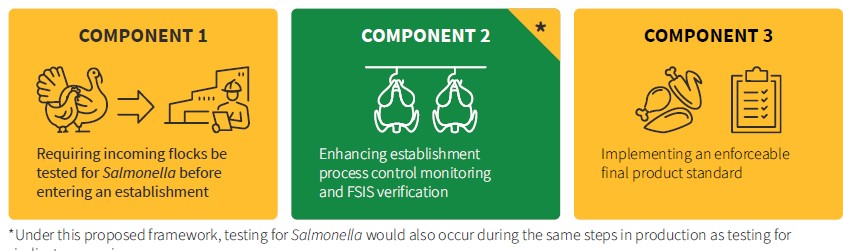

- Advocate. Make all pathogens that can sicken or kill us adulterants. In 1994 Mike Taylor making E. coliO157:H7 and adulterant has saved countless lives and has saved the beef industry from my lawsuits. We can do the same for all food producers, especially chicken, turkey, and pork. Remember, in the 1990’s nearly all the lawsuits I filed were E. coli cases linked to ground beef. Today that is zero. Think about it.

- Educate. Give everyone a thermometer and provide better education to middle and high school teachers and students around food safety and human nutrition policy, not in a dry, technical way, but by sharing engaging history, microbiology, patient stories, and case studies. We need to teach how and why our food can be unsafe and what consumers can do about it.

- Consolidate. Finally, make a single federal agency out of USDA/FSIS, FDA, and the food safety parts of CDC, NOAA, and EPA, to oversee food safety and human nutrition. Making food safety and human nutrition its own agency would help increase governmental accountability, close regulatory loopholes, facilitate the collection and sharing of information and facilitate critical change. I might have a suggestion for someone to run it.

With the CDC estimating 48,000,000 are sickened each year, 125,000 hospitalized, and 3,000 die from food, preventing pathogenic foodborne illness is no simple matter. And, if you consider the millions that are impacted by the lack of adequate and safe nutrition, we have a lot to do. However, it can be done, and the six ideas above are a small start.

“Doing anything is better than doing nothing,” my Marine drill sergeant father used to say. He used to require my brother and I to make our beds every morning and bounce quarters on them. For the longest time I thought this was punishment. But it was not punishment, it was accomplishment, that you could build on for the rest of the day. Doing “little” things, like the six things above, are accomplishments. Doing them starts a process that will continue to make all our lives just a little bit safer.

[Source:

[Source: