The FDA’s somewhat good news on antibiotic use in farm animals (if we believe it)

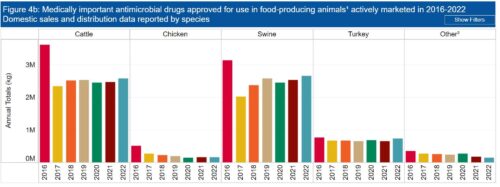

The FDA issued its most recent report on antibiotics late last year: 2022 Summary Report On Antimicrobials Sold or Distributed for Use in Food-Producing Animals, along with Antimicrobial Sales and Distribution Data 2013-2022.

It did this in response to public concerns about antibiotic use in food animals: if antibiotics are used at subtherapeutic doses, they might induce microbial resistance to drugs used to treat diseases in humans.

This is not a theoretical concern. It’s a real problem.

It’s also a problem because the vast majority of antibiotics were used as growth promoters or to prevent infections in animals crowded together—not to treat disease.

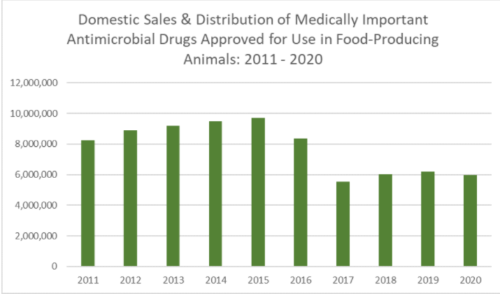

In 2014 or so, the FDA ruled that medically important antibiotics could no longer be used as growth promoters in farm animals. That rule went into effect in 2017.

The FDA’s good news: the amounts of antibiotics used in farm animals has declined since then.

Are medically important antibiotics still used for non-therapeutic purposes?

The report says that since 2017, zero antibiotics are administered for growth promotion.

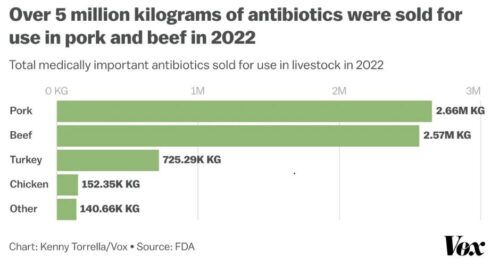

If you wonder whether this is really true (as I do), consider that $11.2 million kilograms of antibiotics were used in food animals in 2022. This is a decrease from the 15.6 million kg used in 2015, but still a lot.

Of these drugs, 63% are administered in feed, and 31% in water.

All antibiotics still used as growth promoters are supposed to be drugs not used in human medicine.

I’m not the only skeptic on this one. See:

I. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s Antibiotics in agriculture: The blurred line between growth promotion and disease prevention.

In an investigation published today, the Bureau revealed how US farm animals are still being dosed with antibiotics vital to human health, despite efforts to curtail such usage and combat the spread of deadly superbugs. We also found that a regulatory loophole means that using antibiotics to make animals fatter – a process known as growth promotion – is technically still possible, despite this practice being banned in January 2017.

II. Nature: Antibiotic use in farming set to soar despite drug-resistance fears. Analysis finds antimicrobial drug use in agriculture is much higher than reported.

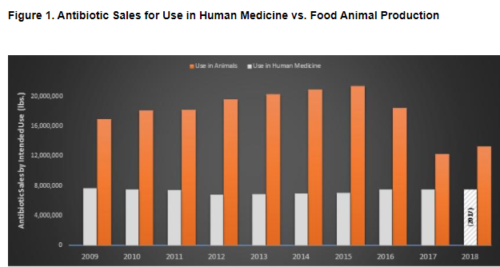

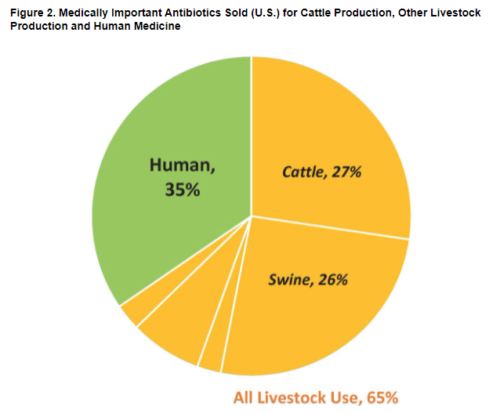

According to an analysis published in September by the Natural Resources Defense Council and One Health Trust, medically important antibiotics are increasingly going to livestock instead of humans. In 2017, the meat industry purchased 62 percent of the US supply. By 2020, it rose to 69 percent.

Does the FDA check? It has guidance for industry on The Judicious Use of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs in Food-Producing Animals, but this guidance is non-binding.

Obviously, the FDA needs to do more. Its officials told Vox:

Veterinarians are on the front lines and as prescribers, they’re in the best position to ensure that both medically important and non-medically important antimicrobials are being used appropriately…We cannot effectively monitor antimicrobial use without first putting a system in place for determining [a] baseline and assessing trends over time.

Vox reports: “The agency right now only collects sales data, and it’s been exploring a voluntary public-private approach to collect and report real-world use data.”

This is not reassuring. The use of antibiotics in animal agriculture is a long-standing issue. It requires political will, big time.