My monthly Food Matters column for the San Francisco Chronicle:

Food is cheap at market, but costs a lot elsewhere

Q: I pay a lot for food, and more each day, but then people like you say our food is cheap because its real costs are “externalized.” Huh? What’s that supposed to mean?

A: Food prices are indeed going up, and I can hardly keep track of the possible causes: natural disasters, crop failures, commodity speculation, corn used for biofuels, lack of research in agriculture, the declining value of the U.S. dollar and just plain greed.

But we Americans still pay relatively less for food than anywhere else because so many of the costs of industrialized food production are “externalized.” We pay for them, but not at the grocery store.

Human costs

I was reminded of externalized food costs when reading about the remarkable efforts of a Salinas teacher to educate children of itinerant farmworkers. The kids are trying to learn under disrupted, impoverished, crowded living conditions. If their parents were paid and housed better, we would pay more for food.

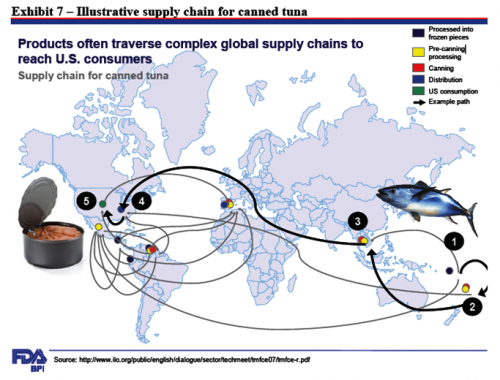

Last summer I visited fish canneries at the far end of the Alaskan peninsula. The fish packers were women from the Philippines, working round the clock for months to send money home to their children and families.

The canneries used to hire Alaskan high school students at wages high enough to put them through college. But to keep prices competitive, the companies reduced wages and imported labor. That money disappeared from the community.

The CEO of a large U.S. meat company told me that if he raised wages by $3, he could hire locals and not have to deal with immigrant labor. But then he would have to raise the price of his meat by 3 cents per pound (I’m not kidding). That amount, he claimed, would price him out of competitiveness.

Environmental costs

Twenty billion dollars of our tax money goes to subsidies for industrial food production every year. Additional tax money is required to clean up the mess created by that system – polluted drinking water, infertile soil, ocean dead zones and overall misery in the surrounding areas.

While driving to give a talk at a college in rural Minnesota last year, I passed within a mile or so of an industrial pig farm. The overpowering smell – an externalized cost – was still on my clothes hours later.

Safety costs

Food safety is one casualty of a food system devoted to low cost. Companies save money by cutting corners on oversight and overlooking safety violations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says food pathogens cause 48 million illnesses, 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths each year.

Some experts say unsafe food costs Americans $152 billion annually – $1,850 for each case in health care and lost wages. Severe illnesses from E. coli O157:H7 can generate more than $1 million in health care costs alone, and ruin lives forever.

To these amounts must be added the costs to food producers of product recalls, continued loss of sales, lawsuits and ruined reputations. Sales of spinach, for example, are only now returning to levels reported before the huge E. coli outbreak in 2006.

Here again, the cost of prevention is minimal for large companies producing large volumes of food. Officials of one vegetable-packing company told me that the impressively comprehensive food safety system they instituted in the wake of recalls raised the cost of their products by only one penny a case (I’m not kidding about this, either).

Despite ample evidence from surveys that consumers are willing to pay more to guarantee safe food, large food producers perceive those few pennies as competitive barriers.

Health care costs

Let’s count obesity as another externalized result of a cheap food system. The cheapest foods are high in calories and low in nutritional value – “junk” foods. When food is cheap, people eat more of it.

Abundant cheap food leads companies to aggressively market their products to be eaten any time, any place and in very large amounts – all of which promote biologically irresistible overeating.

Current estimates of the costs of obesity and its consequent illnesses in health care and lost productivity approach $147 billion annually, almost the same as the cost of unsafe food.

Accurate or not, such numbers provide ample evidence for the need to bring agricultural policy in line with health policy.

To pick just one example: Dietary guidelines say to eat more fruits and vegetables, and cut down on sodas. But the indexed cost of fruits and vegetables has increased by about 40 percent since the early 1980s, whereas that of sodas has decreased by about 20 percent.

The high externalized cost of our present food system is a good reason to reconsider current policies when the Farm Bill comes up for renewal in 2012. Now is the time to start working toward food system policies that will better promote health, safety and human welfare.

Marion Nestle is the author of “Food Politics,” “Safe Food,” “What to Eat” and “Pet Food Politics,” and is a professor in the nutrition, food studies and public health department at New York University. E-mail her at food@sfchronicle.com, and read her previous columns at www.sfgate.com/food.

This article appeared on page H – 4 of the San Francisco Chronicle