The FDA announced this morning that it is proposing a Daily Value (the maximum) for Added Sugars on food labels—10% of calories.

Susan Mayne, FDA’s Director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, explains the rationale: this is the percentage recommended by the Dietary Guidelines and practically every other health authority that has examined the evidence on sugars and health.

Ten percent of calories means 200 calories on a 2000 calorie daily diet, or 50 grams, or 12 teaspoons—the amount in one 16-ounce soda.

If you drink a 16-ounce soda, you have done your added sugars for the day.

If this seems abstemious, consider that 10% of calories is more generous than the amount recommended by the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition:

It is recommended that the average population intake of free sugars should not exceed 5% of total dietary energy for age groups from 2 years upwards.

The World Health Organization’s recent report on sugars and health also views 10% as the absolute maximum:

- In both adults and children, WHO recommends reducing the intake of free sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake (strong recommendation).

- WHO suggests a further reduction of the intake of free sugars to below 5% of total energy intake (conditional recommendation).

The WHO report explains:

The recommendation to further limit free sugars intake to less than 5% of total energy intake, which is also supported by other recent analyses, is based on the recognition that the negative health effects of dental caries are cumulative, tracking from childhood to adulthood…No evidence for harm associated with reducing the intake of free sugars to less than 5% of total energy intake was identified.

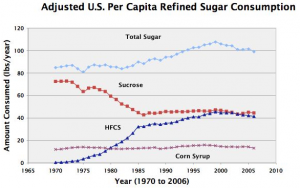

Americans, on average, consume way more than 10% of calories from added sugars, so this recommendation means a sharp restriction.

It means consuming less of sugary products: sodas, baked goods, and all those packaged foods with added sugars.

The proposal is up for comment.

You can bet that there will be plenty.

Congratulations to the FDA for this one. Let’s hope it sticks.

How to Comment

To comment on the proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts Label:

- Read the proposed changes.

- Starting Monday, July 27, 2015, go to Regulations.gov to submit comments.