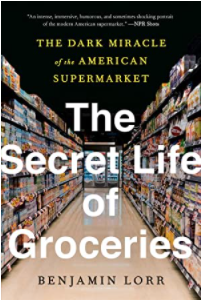

Benjamin Lorr. The Secret Life of Groceries: the Dark Miracle of the American supermarket. Avery/Penguin Random House, 2020.

I don’t know how I missed this one when it came out in mid-2020, but I did.*

I saw a reference to it and thought I ought to take a look, largely because I am gearing up to update my book, What to Eat, in a second edition for Picador/Farrar Straus Giroux.

My book, which first appeared in 2006, is about food issues, using supermarkets as an organizing device.

Lorr’s book, which I expected to be a superficial expose of supermarkets, is anything but.

It is a deep, detailed, personal, and utterly powerful indictment of the human rights violations perpetrated on workers in grocery supply chains: truckers, grocery store clerks, Thai workers on shrimp-catching boats.

The personal comes in because Lorr is an experiential immersion journalist. He embedded himself with a trucker, the fish section of a Whole Foods market, and a Thai fishing boat, as well as spending several years doing interviews. Using the personal stories, he has plenty to say about truly shameless exploitation of low-wage workers in order to keep food costs low.

If you want to understand what low-wage work—or the Great Resignation—is about, here’s an excellent place to start.

This is an important book about food labor issues, but also about how more general systems of exploitation are maintained.

The “more general” leads me to pick one bone with Lorr’s analysis.

For those of us, he says:

Who want to shake the world aware to the fact that we are literally sustaining ourselves on misery, who want to reform, I very much don’t want to dissuade you so much as I want you to consider that any solution with come from outside our food system, so far outside it that thinking about food is only a distraction from the real work to be done.

His book, I’d say, proves just the opposite. Food is his entry point into this topic and would not be there without it.

*I shouldn’t have missed it. It was reviewed in the New York Times. And Charles Platkin, whose work I follow closely, interviewed Lorr when the book first came out.