Proposition 37 take-home lesson: the power of money in politics

The take-home lesson from the defeat of Proposition 37—GMO labeling—is crystal clear.

As Tom Philpott explains in his Mother Jones post,

No fewer than two massive sectors of the established food economy saw it as a threat: the GMO seed/agrichemical industry, led by giant companies Monsanto, DuPont, Dow, and Bayer; and the food-processing/junk-food industries who transform GMO crops into profitable products, led by Kraft, Nestle, Coca-Cola, and their ilk. Collectively, these companies represent billions in annual profits; and they perceived a material threat to their bottom lines in the labeling requirement, as evidenced by the gusher of cash they poured into defeating it.

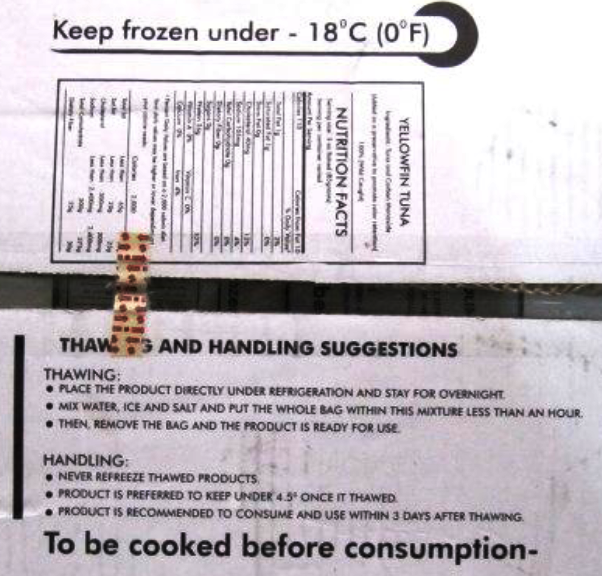

The proof lies in this remarkable graph of poll results produced by Pepperdine University/California Business Roundtable. Polling results started to shift only after the October 1 start of the “No on 37” television ad campaign.

Philpott and others see this defeat as just the beginning of a strong increase in public concern about the role of money in politics.

As for labeling of GMOs: As I’ve said before, proposition 37 deserved support, and GMOs should be labeled.

In a way, it’s hard to understand why the industry thinks it is justified to put $46 million ($46 million!) into defeating a labeling initiative. The world has not come to an end.

In response to European public pressure, McDonald’s, another American company, produces its products without GMOs.

Demands for GMO labeling are not going to go away.

The heavy-handed industry campaign against labeling ought to have some consequences. One is likely to be increasing support for efforts to Just Label It.

Addition:

I’ve just seen the tough analysis by Jason Mark, Editor, Earth Island Journal:

As far as I can tell, the Prop 37 campaign failed to put together a field campaign capable of countering the flood of deceptive ads broadcast by the No campaign…

I don’t understand why the Prop 37 campaigners tried to fight on the airwaves in the first place. From Moment One they knew they would be hugely outspent on TV, radio and web ads…

When you’re the underdog, you don’t go toe-to-toe with the big guy. You have to resort to asymmetrical warfare, guerilla warfare. In electoral politics, that means prioritizing the ground war(organizers and activists) over the air war (paid advertisements)…

the good food movement needs to recommit itself to building power through old-fashioned, Saul Alinsky style organizing.

![poll_copy_0[1]](https://foodpolitics.com/wp-content/uploads/poll_copy_01-300x253.jpg)