How the food Industry exerts influence IV: Science teachers and public health professionals (beef industry)

Two examples of beef-industry attempted influence:

I. Science teachers

This one comes from Wired: Inside the Beef Industry’s Campaign to Influence Kids

Big Beef is wooing science teachers with webinars and lesson plans in an attempt to change kids’ perceptions of the industry.

A beef industry group is running a campaign to influence science teachers and other educators in the US. Over the past eight years, the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (AFBFA) has produced industry-backed lesson plans, learning resources, in-person events, and webinars as part of a program to boost the cattle industry’s reputation.

What is the AFBFA?

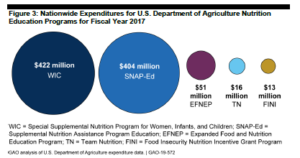

The AFBFA is a contractor to Beef Checkoff, a US-wide program in which beef producers and importers pay a per-animal fee that funds programs to boost beef demand in the US and abroad. In 2024, Beef Checkoff has approximately $42 million to disperse across its initiatives, and a funding request reveals that the AFBFA’s campaign for 2024 is projected to cost $800,000. The allocation of Beef Checkoff funding to programs like this is approved by members of the Cattlemen’s Beef Board and the Federation of State Beef Councils, two groups that represent the cattle industry in the US.

What does this program teach?

One lesson plan provided as part of the program directs students to beef industry resources to help devise a school menu. In another lesson plan students are directed to create a presentation for a conservation agency regarding the introduction of cattle into their ecological preserve. A worksheet aimed at younger students has them practice their sums by adding up the acreage of cow pastures. Another worksheet based around a bingo game aimed at 8- to 11-year-olds asks teachers to “remind students that lean beef is a nutritions source of protein that can be incorporated in daily meals.”

As for the answer to my question yesterday about whether this kind of training works:

According to survey data included in these documents, educators who attended at least one of the AFBFA’s programs were 8 percent more likely to trust positive statements about the beef industry. Some 82 percent of educators who participated in a program had a positive perception of how cattle are raised, and 85 percent believed that the beef industry is “very important” to society.

Again, this is a USDA-sponsored checkoff program. The US Dietary Guidelines on beef call for it to be lean and unprocessed. The checkoff does not.

II. Public health professionals

I received this e-mailed message from a reader who wishes to remain anonymous.

I am a member of the Kentucky Public Health Association and so receive their email newsletters. The Beef Council promotion is fairly new. It is interesting to watch an industry PR campaign with health professionals happen in real time. I’ve also just realized that I don’t believe the Association has policies around sponsorships, something I had not worried about until the past few months.

She forwarded two messages sent to her from the Kentucky Public Health Association. These are announcements from the Kentucky Beef Council: “Happy Nationl Nutrition Month,” and “Fueling Tween and Teens with Strong Minds and Bodies.”

The second is labeled as an advertisement; the first is not.

Both encourage visits to the Beef Nutrition Education Hub to get free continuing education credits and other resources.

Both say:

Thank you to our 38,000 Kentucky Beef Farmers! Fun Fact: Kentucky is the largest beef-producing state East of the Mississippi River

This email was sent on behalf of KY Beef Council and the content within shall be attributed to the sponsor. This email shall not indicate an endorsement on behalf of KPHA.

Copyright © 2023 Kentucky Public Health Association

Comment: The Kentucky Beef Checkoff at work! Regardless of the Kentucky Public Health Association’s protestations, these messages give the appearance of endorsement. It should not be doing this.