More on Dietary Guidelines: San Francisco Chronicle

I write a monthly first-Sunday column for the San Francisco Chronicle. This one is on the latest Dietary Guidelines.

Dietary Guidelines try not to offend food industry

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Q: What do you think of the new Dietary Guidelines that were announced earlier this week? Is there anything very new or different? And how important are these guidelines, anyway?

A: I was stunned by the first piece of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans that I saw online (dietaryguidelines.gov): “Enjoy your food, but eat less.”

Incredible. The federal government finally recognizes that food is more than just a collection of nutrients? It finally has the nerve to say, “Eat less?”

But this statement and others directed to the public do not actually appear in the guidelines. That document repeats the same principles that have appeared in dietary guidelines for decades.

The 2010 guidelines just state them more clearly. (For the news story on the guidelines, go to sfg.ly/gdgsc0.)

Obesity prevention

Its 23 recommendations are aimed at obesity prevention. They focus on eating less and eating better. “Eat better” guidelines suggest eating more vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat milk, soy products, seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, beans, peas, nuts and seeds – all are foods.

But the “eat less” advice is about nutrients: sodium, saturated fat, cholesterol and trans fats. The guidelines even coin a new term for the “eat less” nutrients of greatest concern: “solid fats and added sugars,” annoyingly abbreviated as SoFAS.

Here is one SoFAS guideline: “Limit consumption of … refined grain foods that contain solid fats, added sugars, and sodium.”

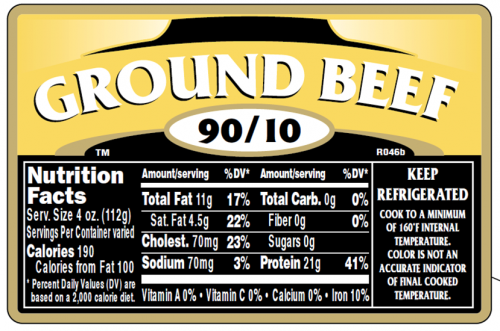

Nutrient-based guidelines require translation. You have to delve deeply into the 95-page document to find the food translations. Eat fewer solid fats? This means cakes, cookies, pizza, cheese, processed and fatty meats, and, alas, ice cream. Less sugar? The major sources are sodas, sports drinks, energy drinks and fruit drinks.

Why don’t the guidelines just say so? Politics, of course.

Official policy

Dietary guidelines are an official statement of federal nutrition policy. They influence everything the government says and does about food and nutrition. The guidelines determine the content of school meals, the aims of food assistance programs and the regulation of food labeling and advertising.

But their most powerful effect is on the food industry.

Why? Because advice to eat less is very bad for business.

Banal as their recommendations may appear, dietary guidelines are hugely controversial. That is why I was so surprised by “Enjoy your food, but eat less.”

Consider the history. In 1977, a Senate committee chaired by George McGovern issued dietary goals for the United States. One goal was to reduce saturated fat to help prevent heart disease. To do that, the committee advised “reduce consumption of meat.”

Those were fighting words. Outraged, the meat industry protested and got Congress to hold hearings. The result? McGovern’s committee reworded the advice to “choose meats, poultry and fish which will reduce saturated fat intake.”

This set a precedent. When the first dietary guidelines appeared in 1980, they used saturated fat as a euphemism for meat, and subsequent editions have continued to use nutrients as euphemisms for “eat less” foods.

Then came obesity. To prevent weight gain, people must eat less (sometimes much less), move more, or do both.

This puts federal agencies in a quandary. If they name specific foods in “eat less” categories, they risk industry wrath, and this is something no centrist-leaning government can afford.

Eat less, move more

So the new guidelines break no new ground, but how could they? The basic principles of diets that protect against chronic disease do not change. Stated as principles, the 2010 dietary guidelines look much the same as those produced in 1980 or by the McGovern committee.

In my book, “What to Eat,” I summarize those basic principles “eat less, move more, eat plenty of fruits and vegetables, and don’t eat too much junk food.” Michael Pollan manages this in even fewer words: “Eat food. Mostly plants. Not too much.”

Everything else in the guidelines tries to explain how to do this without infuriating food companies that might be affected by the advice. And the companies scrutinize every word.

The soy industry, for example, is ecstatic that the guidelines mention soy products and fortified soy beverages as substitutes for meat and as protein sources for vegetarians and vegans.

The meat industry is troubled by the suggestion to increase seafood, even though the guidelines suggest meal patterns that contain as much meat as always.

The salt recommendation – a teaspoon or less per day, and even less for people at risk for high blood pressure – is unchanged since 2005, but stated more explicitly. The salt industry reacted predictably: “Dietary guidelines on salt are drastic, simplistic and unrealistic.”

In a few months, a new food guide will replace the old pyramid. Thanks to a law Congress passed in 1990, dietary guidelines must be revisited every five years. Expect the drama over them to continue.

But for now, enjoy your food.

Marion Nestle is the author of “Food Politics,” “Safe Food,” “What to Eat” and “Pet Food Politics,” and is a professor in the nutrition, food studies and public health department at New York University. E-mail her at food@sfchronicle.com, and read her previous columns at sfgate.com/food.

This article appeared on page H – 3 of the San Francisco Chronicle