Taking sodas out of SNAP: the debate

I’m out of the country for a few weeks (México) and missed the House hearing on whether SNAP-eligible food items should continue to include sugary beverages.

From what I gather, most witnesses opposed any change in the program, with one from the American Enterprise Institute the lone holdout.

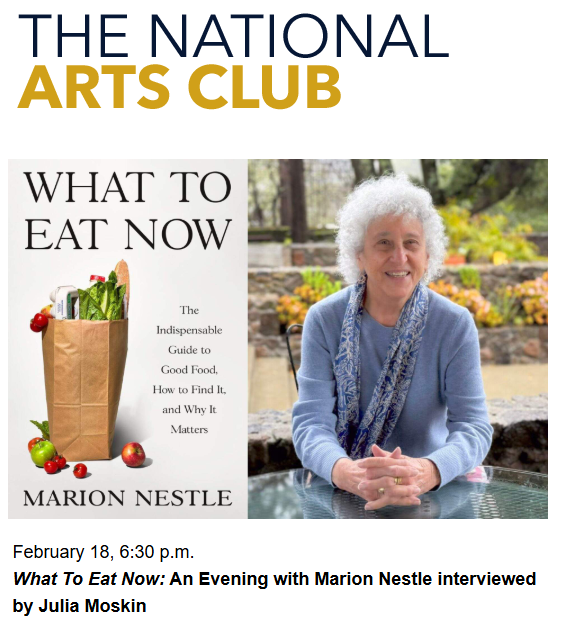

As I discussed in the chapter on SNAP in Soda Politics, I continue to think that taking sugar-sweetened beverages out of the package is a no brainer.

- They are sugars and water and have no nutritional value.

- Tons of research links their consumption to a higher risk for obesity and its consequences.

- SNAP recipients spend a lot of taxpayer money on them.

- SNAP recipients may well have worse diets and higher proportions of chronic disease than equally poor people who do not get SNAP benefits.

- Surveys say that SNAP recipients would not mind this change.

- SNAP recipients can always buy sodas with their own cash.

I recognize that not everyone sees things this way. I suspect that people opposed to this idea are worried that any change to SNAP will leave it vulnerable to cuts, and they could well be right.

Here are their arguments:

- The Hill: Restricting what recipients of SNAP benefits eat won’t fix nutritional issues

- FoodDive: Grocery and food industry to Congress: No SNAP soda ban

- Washington Post: How liberals undermine the food stamp program

- Politico: Few fans for restricting SNAP purchases

Politico provides some sound bites on the topic:

- “Food surveillance violates the basic principles of this great country.” — Rep. David Scott (D-Ga.)

- “What can we do to incentivize rather than punish?” — Rep. Rodney Davis (R-Ill.)

- “If you want to do a pilot program, I’m happy to co-sponsor one at the White House. I’m worried about our president’s eating habits.” — Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Ma.)

The state of Maine, however, has just renewed its request to USDA to remove sugar-sweetened beverages and candy from SNAP-eligible items.

Maine believes the purchase of sugar sweetened beverages and candy is detrimental to the health of the SNAP population, and is antithetical to the purpose of the SNAP program.

SNAP is supposed to be a nutrition program, no? Nutrition is about a lot more than calories (and this from someone who wrote a book about calories).