Annals of Marketing: Coca-Cola innovations

As I keep saying, it’s a Brave New World. Try this one: Coca-Cola launches beverage created with the help of artificial intelligence.

Earlier this year, Becks rolled out the world’s first beer and full marketing campaign made with artificial intelligence. The AB InBev-owned brand said the beer, called Beck’s Autonomous, was selected by AI as its favorite among millions of different flavor combinations it generated.

….For Coca-ColaCreations, the use of AI is a natural step that positions the drink in a way that could pique the interest of younger consumers who will want to try it, before potentially increasing their consumption of other Coca-Cola products. Similar to other beverages released under the Creations platform, the latest beverage doesn’t promote or reveal a flavor profile, such as cola, cherry or vanilla, but rather a mood or experience.

As for mood and experience, we have this: More than the Real Thing: Chinese consumers want emotion and culture, not just drinks – Coca-Cola.

Of course China is very rich in culture and heritage, but beyond this there are also many elements of the lifestyle today that consumers will also link to local culture, such as popular trends locally

…One of these is the rise in popularity of the game League of Legends locally, and with this in mind we launched a limited edition “The Hero Has Arrived” product in collaboration with the game, creating an entire platform for players and consumers to really connect with it—this was also designed to have a unique limited edition flavour with zero sugar, so it remains in line with current trends as well.

Here it is clear that this sort of innovation requires thinking that is less dependent and far beyond just the science of beverage creation—it comes from a focus on understanding local trends, consumers, items and the connections between them to form the culture, and integrating this culture into the innovation.

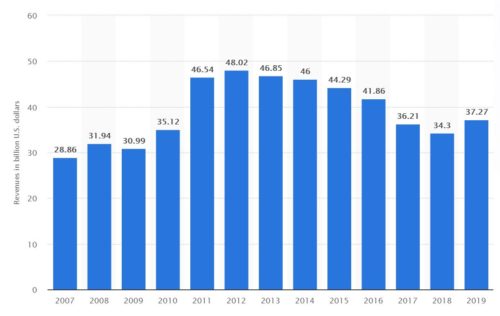

Comment: Yes, Coca-Cola sells bottled water but that’s not how it makes its money. The real money is in sugary beverages and other ultra-processed drinks. I suppose AI is as good as any other marketing expert but I sure hate to see these products flood China. The country is having enough of a problem with its rising prevalence of obesity and related chronic diseases.