Weekend reading: Commercial Determinants of Health

From Oxford University Press:

I was happy to be asked to contribute to this book:

My thanks to Eric Crosbie, who did the heavy lifting on the chapter and also co-authored two other chapters (on trade and investment and on teaching commercial determinants of health.

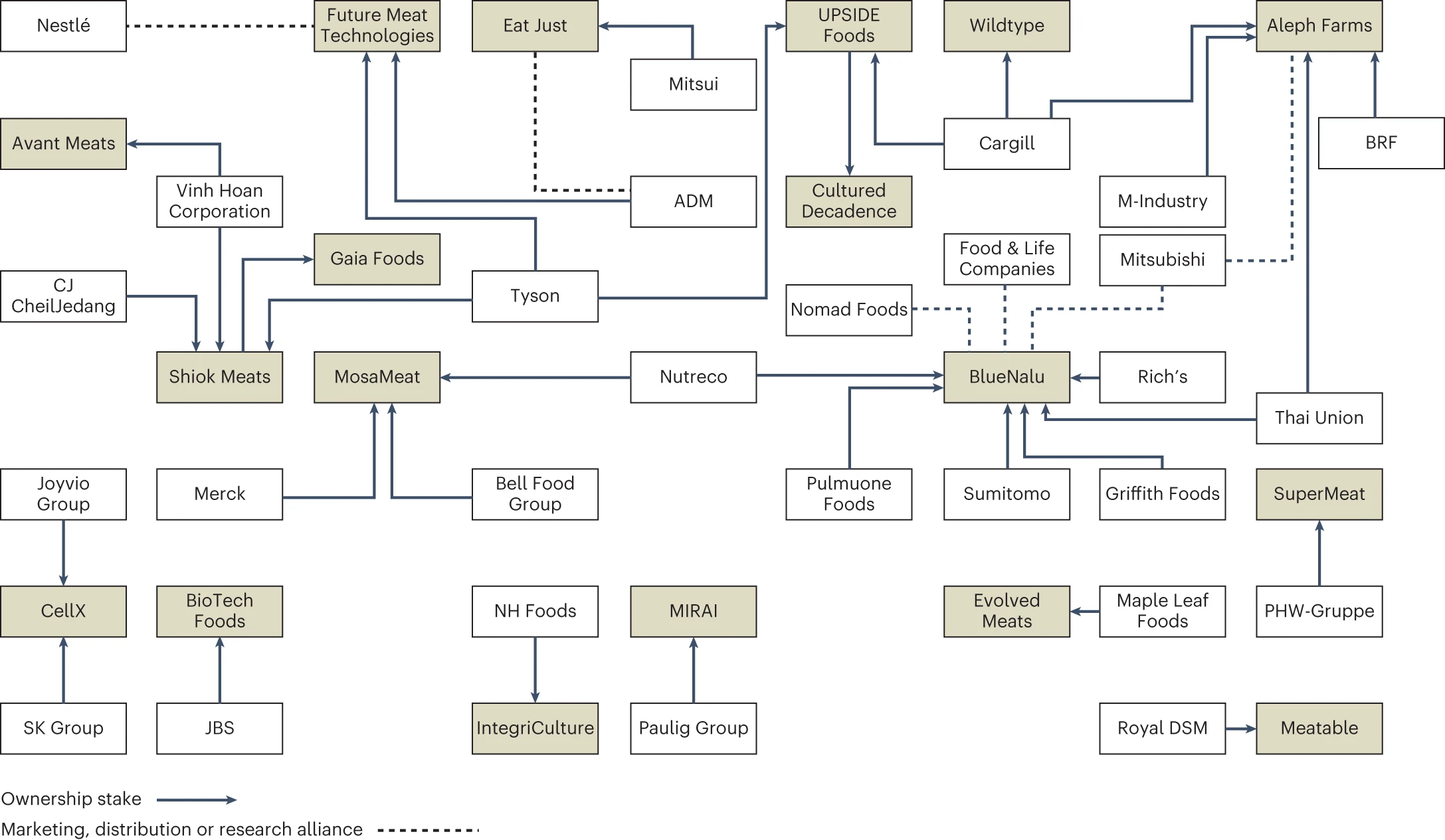

This book brings together multiple authors and perspectives on how corporations selling unhealthful commodities—tobacco, alcohol, and junk food, for example—act to protect sales and marketing, regardless of effects on individual and collective health.

Chapters cover the policies and politics, the ways commercial interessts have taken over culture, how companies influence science, research, and marketing, examples of such influence, analyses of the legal issues, and recommendations for countering corporate actions.

The chapters are so informative and so well referenced that it’s hard to select specific examples. But here’s one from George Annas’ chapter on “Corporations as Irresponsible Artificial People.”

The public health goal is to make the social responsibility of corporations a reality rather than just a feel-good marketing slogan. This will require transforming the corporation from an instrument designed and run to make money while indifferent to polluting the planet and destroying the health of humans to an entity whose money-making must be consistent with preserving the health of the planet and its inhabitants. Central to this objecti8ve is to replace the currfent post-2008 system in which profits are kept by the owners of capital, and losses are socialized by being paid for by governments, most notably for corporations that are “too big to fail.” Any sustainable system requires that both gains and losses are shared by corporations and governments. Sharing gains and lossers will require a restructuring of corporate tax, including a minimum tax for all corporations, but domestic and multinational.

Amen. Everyone needs to understand that food corporations are not social service or public health agencies. They are businesses stuck with responding to the shareholder value movement, which forces them to make profits their first and only priority.

This system needs to change. This book provides the evidence.

Note: I discussed many of these same issues in Unsavorty Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat.

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.