Nordic Nutrition Recommendations: influenced by industry?

A reader who wishes to remain anonymous sent me an account of the development of the new Nordic Nutrition Recommendations, pointing out what they do not contain: a recommendation to reduce ultra-processed foods [Note: this is an updated and slightly corrected version of what was first posted on July 9].

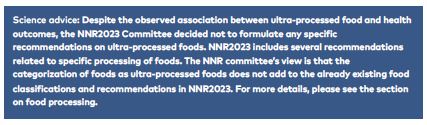

Indeed, on pages 253-255 (this is a long report), you will find this statement:

The backstory here is one of effective food industry lobbying.

The Nordic Nutrition Recommendations do not say: reduce consumption of ultra-processed foods.

The story begins with two authors who were asked to sum up the health effects of ultra-processed foods, and to advise the committee writing the recommendations. They did so. Their initial background paper concluded with these recommendations:

(1) Limit the consumption of ultra-processed foods.

(2) Choose less processed form of foods within each food group when possible.

(3) Cook at home and choose freshly prepared foods when eating out.

The committee revised the background paper. It omitted the three recommendations but concluded:

Recommendations to limit ultra-processed foods, and choose foods of lower processing level, when possible, may enhance and support several of the existing FBDGs [food-based dietary guidelines] and help individuals select more healthful foods that align with the overall NNR2022 [last years Nordic Nutrition Recommendations] guidelines within each food category. For example, such advice would support choosing plain, unsweetened yoghurt instead of flavored, sweet yoghurt; choosing oatmeal or muesli based on grains, nuts, and dried fruits over sweetened, refined breakfast cereals; and choosing chicken breast/thighs over chicken nuggets.

The revised document was opened for public comment and a hearing. A great many representatives of food companies objected to saying anything negative about ultra-processed foods. This Excel spreadsheet lists the 60 people who commented and their main objections.

After the hearing, the committee preparing the recommendations wrote a draft report based on the comments. The section on ultra-processed foods is on pages 152-153. It begins:

There is currently no consensus on classification of processing of foods, including UPFs. The dominating UPF classification (NOVA classification group 4) contains a variety of unhealthy foods, but also a number of foods with beneficial health effects.

It also says:

Health effects. Regular intake of UPF encourages over-eating and intake of foods in the UPF category of the NOVA classification has been suggested associated with increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, depression, and premature mortality …However, no qSRs [qualified systematic reviews] support these suggestions.

These negative views of the UPF concept differ from the views of the background document (however politely stated) and clearly were influenced by the overwhelmingly negative views of food industry representatives.

The draft report also was opened for public comment. These comments also are listed in an Excel document. Some favor the changes benefiting the food industry; others—but many fewer—object to them (these last are summarized in yet another document).

The final Nordic Nutrition Recommendations are somewhat of a compromise between public health and food industry views, but generally favor the food industry position. The new Nordic Nutrition Recommendations are less critical of the UPF concept, but do not say “reduce consumption of ultra-processed foods.”

The NOVA food classification system, which first defined ultra-processed foods, was published by Carlos Monteiro, a professor of public health at the University of São Paulo, and his colleagues in 2009.* About the Nordic recommendations, my informant writes:

I have come to realize that this is not at all about evidence. It’s about power, and who gets to define what’s important in nutrition science. “The establishment” refuses to accept that someone from Brazil, a country they regard as inferior, should be allowed to tell them they have been wrong in their nutritionism-approach. They claim NOVA is based on ideology, not science….And now this is getting in the way of public health.

My take-home lesson: The food industry came out in force on this issue and greatly overwhelmed the few comments of public health advocates. The message here seems clear: public support for reduction of ultra-processed food needs to be widespread, clear, and forceful.

*Definition of ultra-processed foods

- Industrially produced

- Bearing no evident relationship to the foods from which they were derived

- Formulated to be irresistably delicious (if not addictive)

- Usually containing color, flavor, and texture additives

- Often high in salt, sugar, and fat (but these are culinary ingredients that do not in themselves make foods ultra-processed)

- Cannot be made in home kitchens (because they are industrially produced and contain ingredients unavailable to home cooks)

Addition

An additional document was sent to me after this post and the response from nutritionists involved in the NNR, which I posted the following week. It is from the authors of the background document expressing their concerns about the changes made.

[Source:

[Source: