Trump’s $12 billion “gold crutches” to deal with trade retaliation against US agriculture

President Trump says he will fix the retaliation damage his trade policy has caused for agriculture with $12 billion added to USDA programs.

The New York Times quote of the day: “This trade war is cutting the legs out from under farmers and the White House’s “plan” is to spend $12 billion on gold crutches.” –Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Nebraska

The USDA explains that

These programs will assist agricultural producers to meet the costs of disrupted markets. This is a short-term solution to allow President Trump time to work on long-term trade deals to benefit agriculture and the entire U.S. economy.

Politico (behind paywall) quotes USDA Secretary Perdue: “”The programs we are announcing today are a firm statement that other nations cannot bully our agricultural producers to force the United States to cave in.” It explains that the 3-part plan will:

- Provide direct payments to growers and producers of soybeans, sorghum, corn, wheat, cotton, pork and dairy.

- Purchase fruit, nuts, rice, beef, pork and dairy products from U.S. producers for redistribution to federal nutrition assistance programs.

- Put resources toward finding new markets for U.S. farmers to sell their products abroad.

Not everyone loves this idea. Politico quotes Senator Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin):

This is becoming more and more like a Soviet-type of economy here: Commissars deciding who’s going to be granted waivers, commissars in the administration figuring out how they’re going to sprinkle around benefits…I’m very exasperated. This is serious.

It also quotes Rep. Dave Reichert (R-Wash.) observing that the bailout does nothing to preserve market access lost as a result of the tariff policies.

Some in the ag community, they say, ‘That’s great, thank you for the help’ — except that the problem then becomes we’ve lost the market, so how do we get the market back?…That’s the question.

In general, agricultural groups view this as an inadequate short-term fix for a problem that won’t go away until Trump ends the trade war.

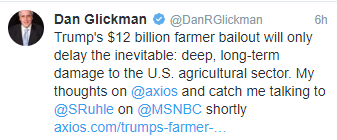

Former USDA Secretary Dan Glickman tweeted a link to a longer statement:

Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-Maine) is introducing legislation to ensure a fairer distribution of the bailouts. How about some trade relief for fishermen?

In the meantime, The Street reports the effect of this plan on the market: Soybean futures for November delivery settled more than 1% higher; Deere & Co. and other farm equipment stocks also went up. CBS News also notes the rise in ag stock prices.

Analysts generally view this as a move to maintain Trump’s base of support among soy and corn producers in the lead up to the midterm elections. It solves a short-term political problem, but does nothing to protect US agricultural markets. See, for example, accounts from

- The New York Times editorial board

- Jerry Hagstrom “The Trade War’s High Costs.”

- Global Meat News

- Associated Press

- Washington Post

- Colbert: Don’t even try to out stupid Donald Trump